Difference between revisions of "Flood mitigation"

ChristineLN (talk | contribs) |

ChristineLN (talk | contribs) |

||

| (8 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

Flood mitigation strategies that incorporate Low Impact Development (LID), traditional stormwater management, and hybrid infrastructure can manage stormwater effectively and reduce flood impacts. | Flood mitigation strategies that incorporate Low Impact Development (LID), traditional stormwater management, and hybrid infrastructure can manage stormwater effectively and reduce flood impacts. | ||

| + | <br clear="all"> | ||

==Types of flooding== | ==Types of flooding== | ||

| Line 21: | Line 22: | ||

! Pluvial (surface) flooding | ! Pluvial (surface) flooding | ||

| | | | ||

| − | [[File:Reflecting-on-the-devastating-2013-storm-mississauga-takes-lead-in-municipal-flood-resilience-the-pointer-be39ea9b.jpg| | + | [[File:Reflecting-on-the-devastating-2013-storm-mississauga-takes-lead-in-municipal-flood-resilience-the-pointer-be39ea9b.jpg|400px|frameless|center]] Street flooding in Mississauga (The Pointer, 2023)<ref>The Pointer. 2013. Reflecting on the devastating 2013 storm, Mississauga takes lead in municipal flood resilience. https://thepointer.com/article/2023-07-30/reflecting-on-the-devastating-2013-storm-mississauga-takes-lead-in-municipal-flood-resilience</ref>. |

| | | | ||

* Caused by intense rainfall that exceeds soil infiltration and storm sewer capacity, especially in urban areas with impervious surfaces. | * Caused by intense rainfall that exceeds soil infiltration and storm sewer capacity, especially in urban areas with impervious surfaces. | ||

| Line 27: | Line 28: | ||

|- | |- | ||

! Fluvial (riverine) flooding | ! Fluvial (riverine) flooding | ||

| − | | [[File:Screenshot 2025-09-22 100405.png| | + | | [[File:Screenshot 2025-09-22 100405.png|400px|frameless|center]]Don River floods DVP (City News, 2024)<ref>City News. 2024. From the scene: Don Valley River floods section of DVP, stranding drivers. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fbyaYZy0d0A&t=68s</ref>. |

| | | | ||

* Occurs when rivers exceed their capacity due to heavy rain or snowmelt, resulting in water overtopping the banks and flowing into adjacent areas. | * Occurs when rivers exceed their capacity due to heavy rain or snowmelt, resulting in water overtopping the banks and flowing into adjacent areas. | ||

| Line 33: | Line 34: | ||

|- | |- | ||

! Coastal (shoreline) flooding | ! Coastal (shoreline) flooding | ||

| − | |[[File:Screenshot 2025-09-19 115121.png| | + | |[[File:Screenshot 2025-09-19 115121.png|400px|frameless|center]]Lake Ontario floods Toronto Island (Toronto Life, 2017)<ref>Toronto Life. 2017. Flooding on the Toronto Islands is terrible—but also weirdly beautiful. https://torontolife.com/life/flooding-toronto-islands-terrible-also-weirdly-beautiful/</ref>. |

| | | | ||

* Driven by storm surges and lake-level rise due to storm surges or seiches. | * Driven by storm surges and lake-level rise due to storm surges or seiches. | ||

| Line 127: | Line 128: | ||

==Modelling Flood Mitigation Potential of Conventional LIDs== | ==Modelling Flood Mitigation Potential of Conventional LIDs== | ||

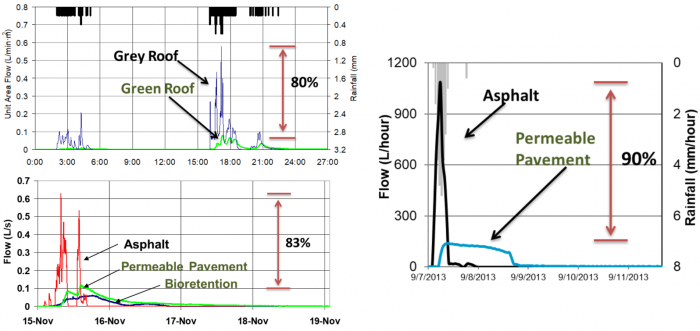

| + | [[File:Screenshot 2025-09-22 113355.png|700px|thumb|right|Peak flow reductions of different LID types during frequent rain events. Top left: Grey and green roof at York University; bottom left: permeable pavement, bioretention and asphalt at Seneca College; right: Kortright permeable pavement and asphalt.]] | ||

TRCA conducted [[modeling]] to evaluate the capacity of different stormwater management measures (LID and Ponds) to mitigate impacts of development on the peak flow and runoff volume. A sub-catchment in Humber River was selected that has an area of 35.7 ha. The existing land use in the sub-catchment is agriculture and the proposed future land use is employment land with 91% total imperviousness. | TRCA conducted [[modeling]] to evaluate the capacity of different stormwater management measures (LID and Ponds) to mitigate impacts of development on the peak flow and runoff volume. A sub-catchment in Humber River was selected that has an area of 35.7 ha. The existing land use in the sub-catchment is agriculture and the proposed future land use is employment land with 91% total imperviousness. | ||

| Line 140: | Line 142: | ||

===Peak Flow=== | ===Peak Flow=== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

*The 25 mm on-site retention using LID measures reduced post-development peak flows generated from 2 to 5 year design storms by over 26%, | *The 25 mm on-site retention using LID measures reduced post-development peak flows generated from 2 to 5 year design storms by over 26%, | ||

*For 50 and 100 year design storms it reduces only 4% and 1% respectively. | *For 50 and 100 year design storms it reduces only 4% and 1% respectively. | ||

| Line 271: | Line 271: | ||

# Smart blue roof systems can regulate rooftop runoff by storing and controlling the release of rainwater | # Smart blue roof systems can regulate rooftop runoff by storing and controlling the release of rainwater | ||

# In addition to peak flow control, blue roof systems can facilitate runoff reduction through rainwater reuse and evaporative rooftop cooling | # In addition to peak flow control, blue roof systems can facilitate runoff reduction through rainwater reuse and evaporative rooftop cooling | ||

| + | |||

===Example 5: [https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2020/09/CVC-Glendale-Rain-Garden-Case-Study.pdf Glendale Public School Rain Garden]=== | ===Example 5: [https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2020/09/CVC-Glendale-Rain-Garden-Case-Study.pdf Glendale Public School Rain Garden]=== | ||

Latest revision as of 20:09, 14 November 2025

Overview[edit]

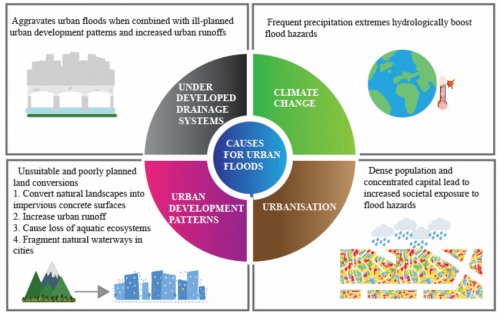

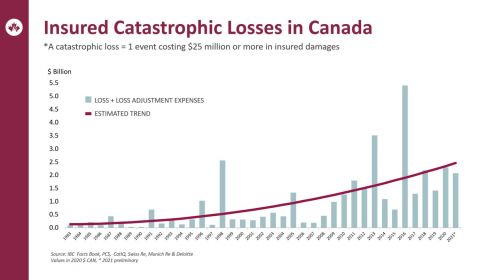

Flooding is a major environmental and economic challenge, particularly in urban areas where impervious surfaces prevent natural infiltration. Flooding can result in traffic interruption, economic loss, infrastructure damage, basement flooding and other undesirable consequences. Climate change is increasing the frequency and intensity of extreme rainfall events, exacerbating flood risks. This will be particularly severe in older areas where the minor system was not designed to today’s standards and/or major drainage system pathways have been altered or do not exist. Catastrophic losses from flooding have been steadily rising in Canada over the last two decades.

"Hydrological changes associated with urbanization are increased storm runoff volumes and peak flows, faster flow velocities and shorter time of concentrations. A reduction in infiltration generally leads to less groundwater recharge and baseflow. The flashy response results in tremendous stresses for the urban stream and downstream receiving areas" (Walsh et al., 2005)[3]

In order to protect downstream properties from flooding due to upstream development, Conservation Authorities establish flood control for future stormwater management planning through regularly updated Hydrologic and Subwatershed Studies that characterize flood flow rates, define the location and extent of flood-prone areas, and assess the potential impact of further urbanization.

Flood mitigation strategies that incorporate Low Impact Development (LID), traditional stormwater management, and hybrid infrastructure can manage stormwater effectively and reduce flood impacts.

Types of flooding[edit]

| Pluvial (surface) flooding | Street flooding in Mississauga (The Pointer, 2023)[4]. |

|

|---|---|---|

| Fluvial (riverine) flooding | Don River floods DVP (City News, 2024)[5]. |

|

| Coastal (shoreline) flooding | Lake Ontario floods Toronto Island (Toronto Life, 2017)[6]. |

|

Mitigative strategies[edit]

Effective flood mitigation strategies fall into three categories: grey infrastructure (traditional engineered solutions), green infrastructure (nature-based solutions), and grey-green hybrids. Cities typically combine measures based on local flood risks, scale, and desired co-benefits such as water quality improvement and urban cooling.

Grey infrastructure solutions[edit]

| Strategy | Flood Mitigation | Additional Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Detention ponds & stormwater basins | Store excess runoff, release gradually | Can improve water quality if designed with wetlands |

| Underground stormwater storage | Prevents sewer overflows, reduces localized flooding | Can integrate water treatment (e.g., Toronto’s Western Beaches Storage Tunnel) |

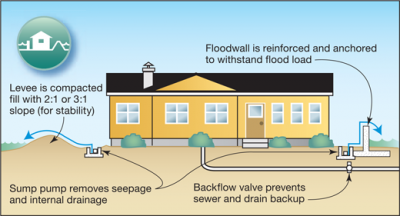

| Levees & floodwalls | Protect against riverine/coastal flooding; also used around buildings for surface flooding | Can be temporarily erected around buildings in response to floods |

Green infrastructure solutions[edit]

LIDs are well suited to address flooding because they can be fit into small areas that may have increased flood risk.

| Strategy | Flood Mitigation | Additional Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Bioretention | Reduces peak flow, increases infiltration | Improves water quality |

| Permeable pavements | Allows infiltration, reduces runoff | Reduces heat island effect |

| Green roofs | Absorb rainfall, delay runoff | Urban cooling, energy savings |

| Riparian buffers | Protect banks, reduce erosion | Habitat, water quality protection |

| Constructed wetlands | Retain/filter stormwater | Habitat, recreation |

| Rainwater harvesting | Collects precipitation, reduces runoff | Water reuse |

| Rain gardens | Reduces on-site runoff | Aesthetic value, pollinator habitat |

Hybrid approaches[edit]

Combining green and grey infrastructure enhances flood resilience. Examples include:

| Strategy | Benefits |

|---|---|

| Stormwater tunnels + LID | Large-scale storage integrated with distributed LID practices. |

| Green streets with subsurface storage | Maximizes infiltration while providing underground detention. |

| Floodable parks / multi-use public spaces | Parks or plazas designed to temporarily store stormwater during extreme rainfall. |

| River restoration with levee setbacks | Reconnecting rivers to expanded floodplains while using engineered levees for protection |

Modelling Flood Mitigation Potential of Conventional LIDs[edit]

TRCA conducted modeling to evaluate the capacity of different stormwater management measures (LID and Ponds) to mitigate impacts of development on the peak flow and runoff volume. A sub-catchment in Humber River was selected that has an area of 35.7 ha. The existing land use in the sub-catchment is agriculture and the proposed future land use is employment land with 91% total imperviousness.

Hydrological model runs were carried out by integrating different stormwater management measures (LID and SWM Pond) for 2-year and 100-year 6-hr AES design storms.

Scenarios evaluated include:

- LID measures that provide 25 mm on-site retention

- SWM pond to control post-development peak flows to pre-development peak flows.

- Combination of scenario 1 and scenario 2

Runoff volume and peak flow reductions were calculated:

Peak Flow[edit]

- The 25 mm on-site retention using LID measures reduced post-development peak flows generated from 2 to 5 year design storms by over 26%,

- For 50 and 100 year design storms it reduces only 4% and 1% respectively.

This shows that LID designed for frequent flows will not significantly reduce the post-development peak flows generated from major storms. In order to meet flood control requirements, traditional LID need to be augmented by some flood storage measures such as dry ponds or underground storage. LIDs can be designed with increased temporary storage to increase detention times. This allows them to function more like underground end-of-pipe facilities (see Honda case study below).

Runoff Volume[edit]

- The 25 mm on-site retention using LID measures can reduce post-development runoff volume generated from 2 to 5 year design storms by over 52 %,

- For 50 and 100 year design storms, runoff volumes are reduced by 33% and 30%, respectively

This shows that the post-development runoff volume generated from major storms conveyed to receiving features can be reduced considerably by implementing LID designed to retain 25 mm.

LID Design for Flood Control[edit]

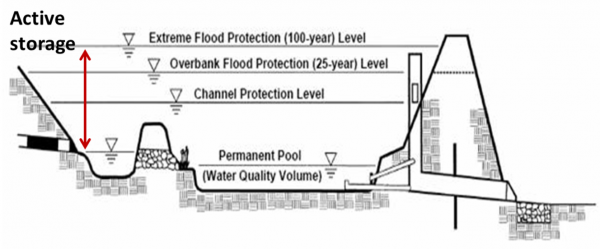

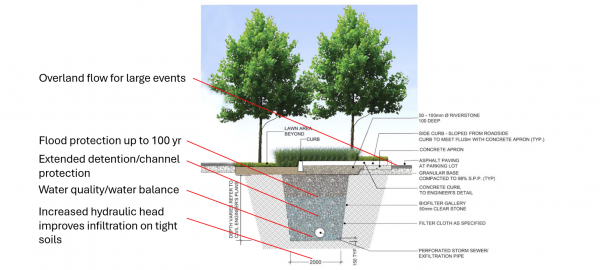

Active storage volume[edit]

LID practices are typically designed to manage more frequent and lower magnitude rainfall events. They work by detaining runoff and releasing it slowly over time. However, larger events can overwhelm the capacity of LID practices. Once their storage capacity is full, the overflow rapidly discharges excess water into storm sewers, thus limiting their ability to mitigate large flood events. LID designed for flood control should integrate large active storage volumes to temporarily store stormwater and slowly release it to streams or downstream sewer systems. The mechanisms by which conventional wet ponds and hybrid stormwater infiltration trench/bioretention facility provide this temporary storage are shown in the figures below:

Kim & Han (2008)[12] and Han & Mun (2011)[13] conducted studies in Seoul, South Korea, to assess the extent to which the installation of rainwater harvesting cisterns could help mitigate existing urban flooding problems without expanding the capacity of the existing urban drainage system. System operational data showed that 29 mm of rainwater storage per square meter of impervious area (3000 m3 cistern in this instance) provided sufficient storage for a one in 50 year period storm without the need to upgrade downstream sewers designed to 10 year storm capacity. Stormwater chambers, infiltration chambers, bioretention and other LID systems designed with large volumes of temporary storage could have similar benefits, while also reducing runoff volumes and providing other co-benefits.

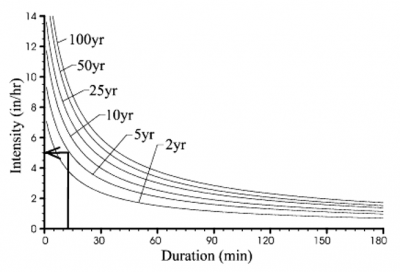

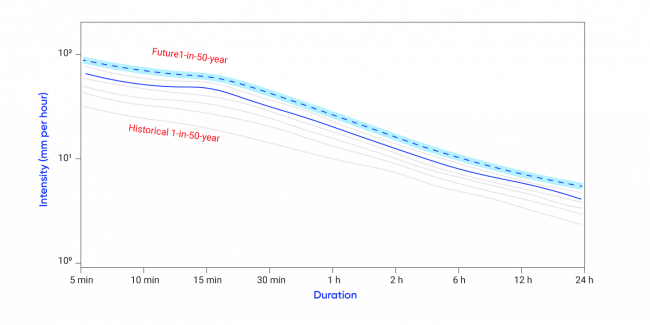

Intensity-Duration-Frequency Curves[edit]

Intensity–Duration–Frequency (IDF) curves are a standard tool in hydrology that describe the statistical relationship between rainfall intensity, storm duration, and frequency of occurrence (return period) to determine the likelihood of extreme rainfall events (Martel et al., 2021)[16].

- Intensity: the rate of rainfall (mm/hr)

- Duration: the length of the rainfall event (minutes to days)

- Frequency: how often a given storm is expected to occur (e.g., a 10-year storm has a 10% chance of occurring in any given year)

IDF curves are developed from long-term rainfall records and models and are widely used to estimate design storms for stormwater management. IDF curves are crucial for sizing LID BMPs because they:

- Define design storms: LIDs must be able to manage runoff from specific return-period events (e.g., 2-year or 10-year storms). IDF curves provide the rainfall intensity and depth to use for those design events.

- Determine runoff volumes: By applying rainfall depth (from IDF data) to a given catchment, the stormwater volume that LIDs need to capture, infiltrate, or detain can be estimated (USDA, 2021)[17].

- Assess peak flows: LID facilities are often designed to reduce peak discharge. IDF curves help simulate storm hydrographs and assess how much peak flow reduction is required (City of Toronto, 2006) [18].

- Account for climate change: Historical data is no longer an accurate predictor of future extreme rainfall (CSA, 2025)[19]. Since IDF curves are based on historical data, climate change-scaled IDFs can be used to design LIDs that are resilient under future rainfall conditions (ECCC, 2025)[15].

To read about IDF curves and best practices, visit:

- https://climatedata.ca/interactive/idf-curves-101/

- https://climatedata.ca/resource/best-practices-for-using-idf-curves/

For more information on IDF curves in relation to climate change, click here.

Pre-treatment[edit]

When designing LID for flood control it is important to consider the need to not only provide extended detention storage but also a means for water to enter the storage reservoir quickly. Incoming flows should also be pre-treated to avoid clogging of media and drainage pipes. Such pre-treatment can be achieved through OGS, catchbasin inserts or high flow cobble inlets, among others. The storage media in the LID facility should have a high void ratio to reduce the potential for clogging with fine sediment that may bypass the inlet pre-treatment controls.

Case Studies[edit]

Below are examples of where LID practices with quantity control components have been used for achieving flood control.

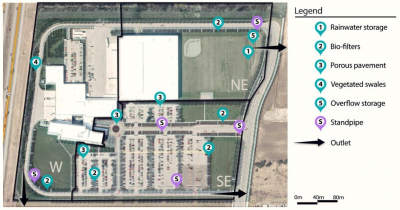

Example 1: Honda Canada Head Office[edit]

The headquarters of Honda Canada is located at 180 Honda Boulevard in Markham, Ontario. The 17.9 ha catchment is divided up into three subcatchments with separate outlets: west (6.3 ha, 53% impervious), Northeast (5.4 ha, 55% impervious), Southeast (6.4 ha, 83% impervious). Overall site imperviousness is 64%. LID practices replaced the need for a stormwater pond, allowing the facility to maintain a large sports field in the northeast portion of the site.

Stormwater Management Criteria

- Quantity Control – meet 100 year storm

- Quality Control – 80% TSS Removal;

- Water Balance – on site retention of first 5 mm of rainfall

- Stream erosion control, 25mm storm released over 72 hours, on-site retention of the first 5mm of rainfall

Stormwater Management Strategy

- The primary practices to achieve on-site runoff retention and peak flow attenuation include a series of large gravel trenches with underdrains (mostly in the SE catchment), a 636 m3 cistern draining water from a 2.4 hectare roof, a small dry pond, permeable pavers and surface swales.

- Underdrain in the trenches is raised 0.15 m off the native soil to provide quality and water balance control through infiltration. Trees and vegetation on top of the gravel filled trenches help reduce runoff through evapotranspiration.

- Underdrain is undersized to increase detention times during flood events. Orifice controls are installed in the downstream sewer to control release rates.

- An automated irrigation system for the playing field and vegetated areas draws stored water from the rainwater cistern to increase capacity during storm events. Outside of the growing season, rainwater from the cistern drains directly to a dry pond which provides temporary storage and release.

Monitoring and Modelling Results

STEP/TRCA conducted a hydrologic monitoring and modelling study of the site in 2012/13 with researchers from The Metropolitan University to assess runoff volume and peak flow reductions. Results showed that, relative to a conventional stormwater approach without LID, runoff was reduced over the study period by between 30% and 35% for the entire site, and by between 58 and 62% in the catchment with a higher density of LID practices. Peak flows were also reduced by 73 to 78%. In the Northeast catchment, 20% of rainfall harvested from the roof was stored and reused for irrigation during the summer months. This reuse volume represented 6% of total site rainfall over 8 months. A hydrologic model calibrated using monitored data showed that the stormwater management system met the design objective of providing quantity control for the post development 100 year storm.

Example 2: Wychwood Subdivision in Brampton[edit]

The Wychwood subdivision is located on Walnut Road in Brampton. The 70 lot residential development covers an area of approximately 5 hectares and has an overall imperviousness of 47%.

Stormwater Management Criteria

- Quantity Control – reduce 2 to 100 year flows to pre-development levels

- Quality Control – 80% TSS Removal;

- Water Balance – match pre-development infiltration volumes

- Stream Erosion control: Manage, detain or re-use all rainfall up to 15 mm over the entire site

Stormwater Management Strategy

- East portion of the site controls minor and major flows through a long bioswale adjacent to the rail line. Driveways are permeable and added top soil helps improve retention of runoff from roofs, which drain to the lawns.

- West portion of the site controls runoff through infiltration swales with orifice controls on underdrains and lot level rain gardens

- All runoff is controlled by LID practices (no dry ponds, wet ponds, or underground tanks)

Monitoring and Modelling Results

- There was 125 rain events monitored and 41 composite samples collected. Modelling was used to determine inflow volumes/rates and water equality loading.

- Low impact development features provide 77 percent volume reductions for events up to 25mm

- TSS load reductions were reduced by 84%

- Event greater than 30 mm showed peak flow reductions of 74%, with a total volume reduction of 59%

- Modelling pre and post development peak flow rates indicated that peak flow targets were met for the 2 to 50 year storms but post development peak flows were *10% greater than pre development peak flows for the 100 year storm.

Example 3: Costco Distribution Centre[edit]

Costco Distribution Centre located within Block 59, Vaughan (City of Vaugh, 2024)[23]. The site has 26.4 ha and the land use is commercial site with an average site imperviousness of approximately 90%;

Stormwater Management Criteria

- Quantity Control – meet Humber River Unit Release Rates;

- Quality Control – 80% TSS Removal;

- Water Balance – Best Efforts to match post to pre;

- Erosion control, 25mm erosion storm released over 72 hours, on-site retention of the first 5mm of rainfall

Stormwater Management Strategy

- A series of sub-surface infiltration chambers providing on-site retention/infiltration of the 5mm storm, water balance to reduce runoff volumes, and storage of the 100-year storm;

- Quality treatment provided using an oil/grit separator immediately upstream of each of the infiltration chambers, filtration through the infiltration chamber, and finally a stormwater management facility provided prior to discharging from the site.

- Final erosion control provided within the stormwater management facility, controlling release rates to maintain the existing condition erosion exceedance values.

- Final design required both LIDs to reduce the overall runoff volumes, but also sub-surface storage chambers to provide quantity control for rare storm events up to the 100-year design storm. Due to large area required for truck parking, limited opportunities for more landscaping to promote evapotranspiration, runoff volumes increased beyond ability of LIDs to negate the need for quantity control.

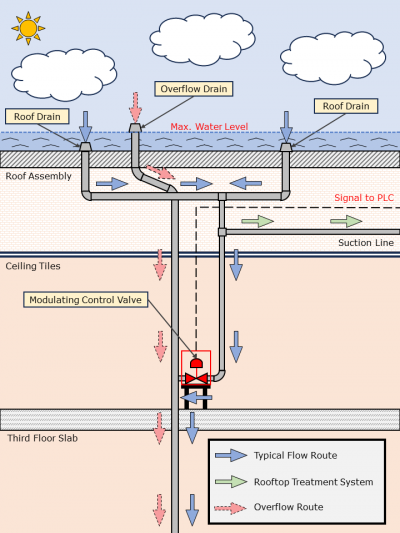

Example 4. Smart Blue Roof System at CVC Head Office[edit]

Glendale Public School area in Brampton faced increased urbanization, limited stormwater controls, and on-site drainage issues that were harming aquatic health in nearby Fletchers Creek, particularly the endangered Redside Dace. To address these concerns, CVC designed a large-scale rain garden using a treatment-train approach, incorporating three swales, conveyance pipes, an underdrain system, and a flow-control valve.

Blue roofs are emerging as an innovative rooftop stormwater management solution that provides flood protection and drought resistance. Instead of quickly conveying stormwater away from a property, blue roof systems temporarily capture rainwater until it either evaporates from the rooftop or is sent to rainwater harvesting storage tanks. A Smart Blue Roof was piloted at the CVC head office in Mississauga. Smart roofs are fitted with weather forecasting algorithms via internet connectivity and automated valves to regulate water discharge from the roof.

Stormwater Management Criteria

- Quantity Control – the rooftop can hold up to 180 mm of precipitation, thus capturing the 100-year storm

- Water Balance – water either evaporates from the rooftop, is sent to rainwater harvesting tank for reuse (can meet non-potable water demands of 8.84 m3/day), or gradually flows into the municipal stormwater system

- Erosion Control – temporary detention and slow release

Stormwater Management Strategy

- Smart blue roof systems can regulate rooftop runoff by storing and controlling the release of rainwater

- In addition to peak flow control, blue roof systems can facilitate runoff reduction through rainwater reuse and evaporative rooftop cooling

Example 5: Glendale Public School Rain Garden[edit]

Stormwater Management Criteria

- Quantity Control – the rain garden was designed to capture runoff from a 27mm storm, covering up to the 90th percentile of the annual rain events in the area.

- Quality Control – reducing total suspended solids (TSS) by 80% before entering Fletcher’s Creek and providing thermal control by cooling runoff before discharging

- Water balance/Erosion Control – increased floodplain storage by a total of 800m3 reducing flooding potential during large storm events.

Stormwater Strategy

- Swales direct surface runoff towards a rain garden.

- The rain garden incorporated trees, shrubs and native plantings as well as native soil amendments and micro-topographic features to encourage adsorption, infiltration and support plant growth.

- Drain pipes under the pathways allow the water level to equalize between garden cells

- Perforated underdrain pipes, placed under the planted area, drained the facility

- A flow control valve was installed at the underdrain outlet to control the amount of water draining into the municipal system located on. During normal operation, this valve is closed to maximize storage and infiltration. Under extreme rainfall events the valve can be opened to release water.

Data Analysis/Modelling[edit]

- Suggest detailed modelling to evaluate how source and conveyance controls could provide a flood control function

- Fieldwork

- Visit sites to record information/interview designer/landowner

- Technical Input/Design Considerations

- If flood control is your goal how does that impact other performance measures?

- How do other combinations of infrastructure impact effectiveness? For example, underdrains, ponding overflow drains, and inlets/outlets may significantly reduce the effectiveness of the practice to retain runoff and also increase costs?

- How would we have designed Elm Drive differently?

- Reducing the potential to mobilize and wash out soil media and erode the practice (this was a big concern raised by Mississauga with the LRT)

- Inlet design to accept the minor and major system

- How to incorporate emergency overflow structures into the design?

- What features can be incorporated to adjust the infrastructure?

Check for related content on Peak flow

References[edit]

- ↑ : Kumar, N., Liu, X., Narayanasamydamodaran, S., Pandey, K.K. 2021. A Systematic Review Comparing Urban Flood Management Practices in India to China’s Sponge City Program. Sustainability, 13, 6346. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116346

- ↑ Insurance Bureau of Canada (IBC). 2022. Severe Weather in 2021 Caused $2.1 Billion in Insured Damage." News & Insights. Accessed: https://www.ibc.ca/news-insights/news/severe-weather-in-2021-caused-2-1-billion-in-insured-damage

- ↑ Walsh, C. J., A. S. Sharpe, and D. A. Burns. 2005. "The urban stream syndrome: Current knowledge and the search for a cure." Journal of the North American Benthological Society 24(3): 706–723. https://doi.org/10.1899/04-028.1

- ↑ The Pointer. 2013. Reflecting on the devastating 2013 storm, Mississauga takes lead in municipal flood resilience. https://thepointer.com/article/2023-07-30/reflecting-on-the-devastating-2013-storm-mississauga-takes-lead-in-municipal-flood-resilience

- ↑ City News. 2024. From the scene: Don Valley River floods section of DVP, stranding drivers. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fbyaYZy0d0A&t=68s

- ↑ Toronto Life. 2017. Flooding on the Toronto Islands is terrible—but also weirdly beautiful. https://torontolife.com/life/flooding-toronto-islands-terrible-also-weirdly-beautiful/

- ↑ McNally. 2017. Western Beaches Tunnel – Toronto, ON. http://mcnally.ca/tunneling-projects/western-beaches-tunnel-toronto/#:~:text=Project%20Outline,pump%20station%20at%20Strachan%20Avenue.

- ↑ Reduce Flood Risk. 2022. Construct a floodwall barrier. https://www.reducefloodrisk.org/mitigation/construct-a-floodwall-barrier/

- ↑ Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates Inc. ND. Corktown Common. https://www.mvvainc.com/projects/corktown-common

- ↑ Ontario Ministry of Environment. 2003. Stormwater Management Planning and Design Manual. https://www.ontario.ca/document/stormwater-management-planning-and-design-manual/stormwater-management-plan-and-swmp-design

- ↑ https://www.toronto.ca/ext/digital_comm/pdfs/transportation-services/green-streets-technical-guidelines-document-v2-17-11-08.pdf

- ↑ Kim, Y., & Han, M. (2008). Rainwater storage tank as a remedy for a local urban flood control. Water Science and Technology: Water Supply, 8(1), 31-36.

- ↑ Han, M. Y., & Mun, J. S. (2011). Operational data of the Star City rainwater harvesting system and its role as a climate change adaptation and a social influence. Water Science and Technology, 63(12), 2796-2801.

- ↑ Bentley StormCAD CONNECT Edition Help. N.D. I-D-F Curves.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC). 2025. IDF Data and Climate Change. https://climatedata.ca/resource/idf-data-and-climate-change/

- ↑ Martel, J.-L., Brissette, F. P., Lucas-Picher, P., Troin, M., & Arsenault, R. 2021. Climate change and rainfall intensity–duration–frequency curves: Overview of science and guidelines for adaptation. Journal of Hydrologic Engineering, 26(10), 03121001. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)HE.1943-5584.0002122

- ↑ USDA. 2021. Estimating Runoff Volume and Peak Discharge. https://directives.nrcs.usda.gov/sites/default/files2/1712930818/31754.pdf

- ↑ City of Toronto. 2006. Wet Weather Flow Management. https://www.toronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/9191-wwfm-guidelines-2006-AODA.pdf

- ↑ CSA, 2025. CSA 231:25 Developing and interpreting intensity-duration-frequency (IDF) information under a changing climate. https://www.csagroup.org/store/product/2431590/?srsltid=AfmBOopkRT3cosyCstZMacCmlthJxgfo6w6aFIXyuEExGmyBT8zw1vMs

- ↑ City of Clearwater. 2025. Help Keep Clearwater's Stormwater Clean. https://www.myclearwater.com/My-Government/0-City-Departments/Public-Works/Help-Keep-Clearwaters-Stormwater-Clean

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 STEP. 2015. Hydrologic Assessment of LID Honda Campus, Markham, ON. https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2015/07/Honda_TechBrief_July2015.pdf

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 STEP. 2020. Wychwood Subdivision, City of Brampton Low Impact Development Infrastructure Performance and Risk Assessment. https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2020/06/Wychwood-Report.pdf

- ↑ City of Vaughn. 2024. Costco wholesale corporation zoning by-law amendment. https://pub-vaughan.escribemeetings.com/filestream.ashx?DocumentId=166701

- ↑ City of Mississauga. 2024. Mississauga is home to Canada’s first CSA-compliant smart blue roof.https://www.mississauga.ca/city-of-mississauga-news/news/mississauga-is-home-to-canadas-first-csa-compliant-smart-blue-roof/

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 STEP. 2020. Glendale Public School Rain Garden: Design and Build Overview. https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2020/09/CVC-Glendale-Rain-Garden-Case-Study.pdf.