Plant lists

Vegetation is a big opportunity to maximize the co-benefits of biodiversity and amenity in LID practices. Planting plans can be formalized or naturalized to suit the surrounding style. In addition to aesthetic qualities, plants have specific functions in several LID practices. These include promotion of infiltration, treatment of pollutants[1] and stabilization of soil. When selecting plants for an LID practice, aim for species with high functionality, survivability, suitability and availability. Landscape professionals should use these lists as guides, taking into consideration the appropriate planting zone, the size of the planting area versus size of the plant at maturity, tolerances to shade, pollution, drought and periodic inundation, maintenance requirements and adaptability.

Rain-Ready Landscapes[edit]

Landscapes that use native plants; including trees, graminoids, shrubs/bushes, tall grasses and perennials to aid is both capturing and 'soaking up' rainwater can help reduce flood risk, build climate resilience, improve water quality and provide habitat for pollinators. There are 3 major types of 'rain-ready landscapes' to choose from when adopting the use of plants in LID practices:

- Rain Gardens - planted shallow depression with rainwater collected from roofs, rain barrel overflows/rainwater harvesting devices and allows water to drain into the surrounding ground within 24 hrs. Generally landscaped with a variety of suitable native plants, that can also benefit pollinator species.

- Infiltration Trenches and Soakaways - Gravel filled pit in this case to collect and transport water from a downspout or rainwater harvesting practice to fit lot-level properties and generally landscaped with river stone, native plants and other decorative rocks or sod. Allows water to drain into the surrounding ground within 24 hrs.

- Bioretention and Bioswales - long trench with gently sloping sides that collects rainwater from impermeable surfaces generally parking lots, boulevards, right-of-ways, etc.) and drains water within 24 hrs. Generally tall grasses and long grasses are planted in the middle and along the bottom part of the swale to aid in reducing the velocity of water entering the practice and to help filter out pollutants.

- Stormwater Tree Trenches - linear tree planting structures that feature supported impermeable or permeable pavements that promote healthy tree growth while also helping to manage runoff. They are often located behind the curb within the road right-of-way and consist of subsurface trenches filled with modular structures and growing medium, or structurally engineered soil medium, supporting overlying sidewalk pavement. Retains and filters out pollutants and salt from urban sites and then allows water to drain into the local municipal storm swear system after a major storm event to help reduce peak flow of water entering into the system and reduces the likelihood of an overwhelmed storm sewer or local surcharge.[3]

How to Choose the Right Plants[edit]

To help you select appropriate plants for your site, we've developed tables to indicate the suitability for use in LID features (see page links under Plant Selection).

- For resilient and robust planting, native species which can tolerate periods of drought and periodic inundation are recommended.

- Woody and evergreen plants should not be planted in any portions of the LID facility to be used for snow storage during winter months.

- Trees and shrubs should be offset from inlets and overflow outlet locations, and lowest-elevation portions of the LID facility, where sediment, trash and natural debris will accumulate, to ensure access for completing routine inspection and maintenance tasks is not hindered.

- Trees should not be planted directly over underdrain perforated pipes and may be better located at the perimeter of LID facilities instead.

- While it is not always necessary to use an exclusively native planting palette, invasive non-native plants (i.e., invasive exotics) should not be planted in LID practices.

Plant Selection[edit]

Note: These pages contain a lot of images and content and will likely take a little longer to load than usual.

Planting Zones[edit]

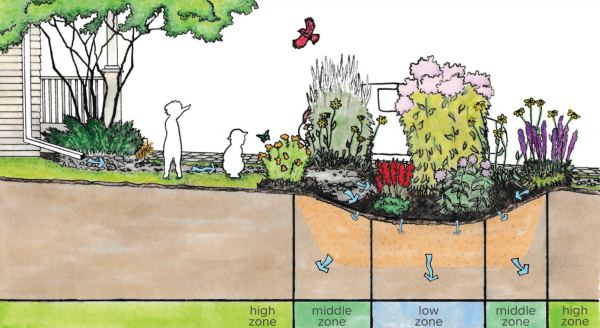

There are three primary zones in a 'rain-ready' LID feature/landscape. These can be seen below:

- Low Zone: Lowest area of the feature, along the bottom of the planted area and is the area that gets fully inundated with water during rain events or heavy runoff leveles enter. Plants that should be chosen here prefer moist soils and should be rated a "3" when referencing our STEP tables above.

- Middle Zone: Middle zone of feature, which can still possess higher soil moisture levels, but that doesn't persist as long as the levels seen in the Low Zone. Plants that should be selected for this area prefer alternating wet and drier periods and should be rated a "2" when referencing our STEP tables above.

- High Zone: High area of the feature in question and as a result its soil moisture levels are very low and it is the driest section of the planted area. Plants selected should have good drought tolerance and should be rated a "1" when referencing our STEP tables above..

Plant Characteristics[edit]

Soil moisture[edit]

Plant species are adapted to specific levels of moisture to achieve establishment and sustained growth. Soil moisture has been characterized by three categories: dry (1), moist (2) and wet (3). Some plants can tolerate a wide range of moisture regimes, whereas others perform optimally in a more narrow range of soil moisture conditions. Species ranked with a dash between two numbers can tolerate a range of conditions.

Shade tolerance[edit]

Plant species react differently to varying levels of sunlight and shade. Plant adaptations to these parameters are referred to in terms of degree of exposure. Most of the LID practices will be installed in newly developed areas, thereby providing exposure to full sun, meaning at least 6 full hours of direct sunlight for plantings. As trees develop over several years, or if an LID practice is installed in an area where there are existing trees or buildings providing partial shade, plants adapted to 3 to 6 hours of sunlight exposure should be used. Plants tolerant of full shade require less than 3 hours of direct sunlight each day. However, some shade-adapted species come into leaf early in the growing season in order to take advantage of full sunlight before tree leaves emerge and create shade.

Our tables indicate whether the species in question is tolerant of shade at all. For more information, consult the sources listed below.

Drought tolerance[edit]

These categories represent broad generalisations regarding drought tolerance.

Salt tolerance[edit]

The low, medium and high categories indicate the tolerance of plant species to salt exposure and/or uptake. Plant species with low salt tolerance should not be used in any LID practice receiving runoff from salted roads and parking lots. Species with medium salt tolerance can be utilised in LID practices that will be receiving road runoff but should not be in the line of salt spray or be receiving the bulk of the runoff. Species with high salt tolerance should be planted in LID practices that receive road or parking lot runoff that routinely contains road salt. Few plants are truly halophytic or “salt-loving”. In most cases, elevated salt levels are temporary and precipitation quickly dilutes and removes salt from the soil profile. The plant lists below include recommended species for LID practices likely to receive road or parking lot runoff.

Compaction and pollution tolerance[edit]

Development nearly always causes compaction of on-site soil, and bioretention facilities in road-right-of-ways should be pollution tolerant.

STEP stars[edit]

These are species which have demonstrated good performance in projects designed, installed and monitored by the Sustainable Technologies Evaluation Program.

| Plant characteristic | Potential benefit to LID performance |

|---|---|

| Plant mass | Higher biomass consumes more nutrients (decreases nutrient discharge from bioretention) and increases transpiration rate. |

| Growth rate | Higher growth rate consumes more nutrients, particularly in combination with root characteristics as below. |

| Root lipid content | Higher root lipid content has been associated with increased plant uptake of organic contaminants such as polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) |

| Root length | Longer roots are associated with plants consuming more nutrients and preserving hydraulic conductivity of the filter media. |

| Root mass and thickness | Larger overall root mass and many dense fine roots are associated with increased nutrient uptake by plants. Thicker roots help to preserve hydraulic conductivity of the media. |

| High-nutrient tolerance | Plants adapted to high nutrient environments are likely to uptake nutrients at a higher rate. |

Planting Design[edit]

Whatever the choice of style, it is essential that the surrounding context is taken into account. While a planting design can have a natural appearance, the landscape should never appear haphazard or messy. The aesthetic goal is to achieve a visual sense of fit and scale with the site. The design should be intentional, appropriate and pleasing to the eye and consider the following:

- Maintain visual interest throughout the seasons

- Use of selective species palate

- Use of one or two species or elements to create an accent

- Consistency in plant placement and spacing; incorporating mass groupings, repeating plant groupings, materials and/or design elements

- Avoid sparsely spaced greenery; the planting beds should be fully vegetated once mature

- Consider habitat attributes of plant material

- Enhanced LID function related to pollutant uptake, temperature mitigation, filtration, and evapotranspiration

To help you select appropriate plants for your site, we've developed tables for graminoids, perennials, shrubs, climbing plants, trees and turf focusing on their suitability for implementing LID practices and their aesthetic appeal.

Basic principles[edit]

The basic principles of landscape design that should be considered in the creation of any planting plan, no matter how small, are described below. For projects that don't require a landscape architect, LID proponents may have to engage in small-scale landscape design. Not all of the following principles need to be applied in each case, but a basic understanding of each provides guidance. The manner in which these principles are applied creates a particular aesthetic.

Unity and Simplicity[edit]

Unity and simplicity in planting design is essential to create an appealing aesthetic. This can be achieved through repetition and consistency. The landscape associated with an LID practice needs to convey that all parts of the planting design fit together to make a whole. The repetition of groups of plants or the character of elements (ie. height, size, texture, and colour) throughout the landscape design can assist on creating a sense of unity in the landscape.

Whilst repetition is a key element used to achieve unity, it is important not to overuse this technique as the result can become monotonous. A landscape design that employs a variety of species in groupings that are repeated throughout a site assists in achieving unity and interest. In contrast, a design that uses just two or three species repeated throughout the entire LID practice may be monotonous.

There is often one visually dominating item or component in a landscape design. Every other component in the design should then be subordinate to this single, dominating focal point. Properly selecting and setting this one focal point in a view should evoke a feeling of satisfaction and pleasure. [6]

Variety and Rhythm[edit]

The subtle varying of contrast in line, form, texture or colour can attract attention to a design without inhibiting the overall unified appearance of the design, particularly if there is a smooth, gradual and progressive change in the design element. If applied sparingly, the result can be an increased attraction to the overall composition. [7]Moreover, the creation of sequence may be achieved by using gradation (e.g. the progressive changing of sizes of components or intensity of textures) or by using fixed repetition (i.e. the repeating of an element on a constant spacing) or by using alteration (i.e. the alternating of contrasting or graded colours and textures). When done successfully, the designer creates a sense of movement or flow through a design. [6]

Grouping/massing[edit]

Planting different species as single individuals can create a disjointed and un-natural aesthetic in a landscape design. Plants should be placed into groupings of varied numbers (e.g. groups of 3, 5 or 7) to create a mass, which can create a much greater visual appeal. One way to create a grouping is by beginning with a larger specimen, and then adding smaller species with complementary textures, colours and shapes. To create a seasonal grouping, evergreen species, and species with dormant season distinctiveness (ie. form, height, colour) should be included.

Balance[edit]

Balance must generally equalize the overall impact of each of the different design elements so that a visually harmonious composition results. [6] Balance in a landscape design can be either symmetrical or asymmetrical. A symmetrical design is one that exactly duplicates itself along an axis. The informal nature of many LID practices tends to promote the application of the asymmetrical balance approach. This is achieved through the irregular placement of plant groupings along an imaginary axis so that the resulting mass is balanced.

Scale/proportion[edit]

Scale and proportion simply refer to the size of the elements, objects and spaces of the landscape in relation to one another, to the LID site and to its surroundings. While there are no rules dictating how this principle is to be achieved, it is important to consider scale and proportion when designing. The relationship in size between components must b relative, or the result can be a lack of harmony in the design.[8] For example, the placement of a large tree in a stormwater planter would be out of scale for this site condition, while the planting of an individual ornamental flower species may appear insignificant in a bioretention cell. Some plant materials may require management (thinning, pruning) in order to maintain the scale and proportion of the intended design over time.

Colour[edit]

Colour animates a landscape design. It is affected by light at different times of the day and changes throughout the seasons. Flowers, fruit, leaves or bark of vegetation contribute to colour variation; in response, the designer should understand the details of the life cycle of the plants to be utilized and include plants that flower at different times of year. Colour theory dictates that warm colours (red, orange, yellow) take prominence in the view, while cool colours (green, blue, violet) recede. Colour also has an emotional impact:

- red = strong

- green = tranquil

- blue = dignified

- violet = sophisticated

- brown = earthy

- gray = somber

- black = serious

- orange = exuberant

- yellow = positive

- white = pure [9]

Colour can be used in developing unity, repetition and balance in a landscape design, and to direct the eye to a focal point, if desired.

Texture[edit]

The designer should be aware of the texture of the planting materials specified. An appealing aesthetic can be achieved by contrasting fine textured vegetation, such as grasses, sedges, with coarser texture species. However, in exploring design solutions it is important to understand the distance from which the LID practices will be viewed, and to mass vegetation textures accordingly when applying this element to the design. Using both coniferous and deciduous vegetation helps create visual appeal throughout the seasons.

Line[edit]

Straight lines represent clean, more formal organizing elements in a design, and they imply a sense of direction and movement. Curved, organic lines promote a more ‘natural’ aesthetic. In either case, clean and contrived shapes have a greater visual interest than weak shapes or indistinct edges.

Form[edit]

Form describes natural shape of an individual plant. The variety of forms include weeping, globular, spreading or columnar. The form of plants should be considered both individually and as they relate in the composition of the design.

Features[edit]

Features incorporated into planting designs, such as benches, stones, paths, and works of art, can make LID spaces more aesthetic, enjoyable and multi-functional.

Planting plans and specifications[edit]

A qualified landscape architect should prepare documents in coordination with engineering design, including tender documents that encompass site development, soil preparation and earthworks. Plans are prepared on a site-specific basis, incorporating planting layout, species composition and spacing. In addition, landscape plans should include construction details and pertinent notes specifying site supervision, monitoring and maintenance.

Early initiatives and successes are more likely to be public, commercial or industrial applications as there is a higher requirement for landscape professionals to be involved and usually a greater opportunity to control and monitor initiatives. Contracts for LID practices may need to be structured slightly differently than a standard construction contract in order to address the long term function of the LID practice, including provision for an extended warranty period.

- Vegetation must meet Canadian Standards for Nursery Stock, 9th Ed[10].

- Seed planting is not recommended for low impact development.

- Plants should be container grown, balled and burlapped or wire basket.

| Deciduous Trees | 45 mm calliper |

| Coniferous Trees | 175 cm height |

| Deciduous Shrubs | 60 - 80 cm height |

| Coniferous Shrubs / Broadleaf Evergreens |

|

| Perennials and grasses | #1 or 1 gal. container stock |

| Vines | #1 or 1 gal. container and staked |

Plant Installation[edit]

Plants should be kept in their containers until they are to be installed, which should take place as soon as possible upon completion of the grading and installation of drainage structures. In addition to the planting plan, plant installation details for herbaceous plants, shrubs and trees should be followed per municipal and landscape industry standards, specifications, and guidelines. Avoid staking unless necessary (ie. vandalism or high wind exposure). If staked, then the ties should be a biodegradable web or burlap and removed after the first growing season. If any plant substitutions are required, then the contractor or contract administrator should defer to the designer or municipal agency to make the substitution.

See Also[edit]

- Plant lists

- Bioretention

- Bioswales

- Enhanced grass swales

- Green roofs

- Rain gardens

- Stormwater planters

- Stormwater tree trenches

- Swales

- Vegetated filter strips

- Wetlands

External resources[edit]

| Organization | Coverage | Types of Material | Website |

|---|---|---|---|

| Credit Valley Conservation | Ontario | Native Grasses, Ferns, Shrubs, Small Trees | https://cvc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/com_lo_rain-ready-guide_20220328-FINAL3.pdf |

| Watersheds Canada | Canada / Ontario | Native Grasses, Ferns, Shrubs, Trees, Vines | https://watersheds.ca/plant-database/ |

| Columbia University, University of Maryland, Smithsonian Institute1 | North eastern USA and Canada | Native and non-native trees and shrubs | http://leafsnap.com/species/ |

| Louisiana State University | USA | Grasses, Ferns, Herbaceous, Shrubs, Trees, Vines, Ornamental | http://onlineplantguide.com/Index.aspx |

| United States Department of Agriculture | USA | Grasses, Ferns, Herbaceous, Shrubs, Trees, Vines, Ornamental | https://plants.usda.gov/java/ |

1. Leafsnap is an on-line field guide, available as a free mobile app that uses visual recognition software to help identify tree species from photos of their leaves, flowers and fruits. [11]

See Also[edit]

- Planting design

- Bioretention

- Bioswales

- Enhanced grass swales

- Green roofs

- Rain gardens

- Stormwater planters

- Stormwater tree trenches

- Swales

- Vegetated filter strips

- Wetlands

- ↑ Hunt, W. F., Lord, B., Loh, B., & Sia, A. (2015). Plant Selection for Bioretention Systems and Stormwater Treatment Practices. Singapore: Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-245-6

- ↑ CVC. 2022. Native Plants for Rain-ready Landscapes. Plant these native wildflowers, grasses, shrubs and groundcovers to help manage stormwater – beautifully. cvc.ca/GreenYourProperty. https://cvc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/com_lo_rain-ready-guide_20220328-FINAL3.pdf.

- ↑ CVC. 2022. Native Plants for Rain-ready Landscapes. Plant these native wildflowers, grasses, shrubs and groundcovers to help manage stormwater – beautifully. cvc.ca/GreenYourProperty. https://cvc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/com_lo_rain-ready-guide_20220328-FINAL3.pdf.

- ↑ CVC. 2022. Native Plants for Rain-ready Landscapes> plant these native wildflowers, grasses, shrubs and groundcovers to help manage stormwater - beautifully. cvc.ca/GreenYourProperty. https://cvc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/com_lo_rain-ready-guide_20220328-FINAL3.pdf

- ↑ Muerdter, C.P., C.K. Wong, and G.H. LeFevre. 2018. Emerging investigator series: the role of vegetation in bioretention for stormwater treatment in the built environment: pollutant removal, hydrologic function, and ancillary benefits. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 4(5): 592–612. doi: 10.1039/C7EW00511C.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Landscape Design Manual, Landscape Ontario (2014) Page 52

- ↑ Landscape Design Manual, Landscape Ontario (2014) Page 51

- ↑ Landscape Design Manual, Landscape Ontario (2014) Page 53

- ↑ Landscape Design Manual, Landscape Ontario (2014) Page 55-55

- ↑ https://cnla.ca/uploads/pdf/Canadian-Nursery-Stock-Standard-9th-ed-web.pdf

- ↑ Columbia University, University of Maryland, Smithsonian Institute. 2018. Leafsnap. http://leafsnap.com/species/