Wetlands

Natural wetlands are ecosystems that have developed over time, providing diverse habitats and naturally filtering water through complex biological and physical processes. Constructed wetlands, on the other hand, are designed and built to mimic these natural functions, targeting specific water quality goals and pollutant removal. They are a cost-effective and efficient method widely used in North America to treat various wastewaters, such as stormwater, sewage, and agricultural runoff. The Ontario Wetland Evaluation System defines wetlands as:

"Lands that are seasonally or permanently flooded by shallow water as well as lands where the water table is close to or at the surface; in either case, the presence of abundant water has caused the formation of hydric soils and has favoured the dominance of either hydrophytic or water-tolerant plants. The four major types of wetlands are swamps, marshes, bogs, and fens."[1]

Wetlands can contribute to[2][3]:

- Enhanced biodiversity

- Enhancing recreational and educational opportunities and aesthetics

- Improving water quality and helping to meet TSS reduction targets

- Storing water and attenuating floods

- Carbon sequestration[4]

Case studies are available for wetlands used in LID systems.

Planning considerations[edit]

Constructed wetlands differ based on how water travels through the system[5][6][7]:

- Free-water surface flow wetlands have water exposed on the surface, which provides excellent water quality treatment but may pose health and safety risks. Free-water surface flow wetlands are most commonly employed for stormwater treatment and are similar to SWM ponds in function and design. However, ponds and wetlands differ by the extent to which shallow zones for wetland plants are incorporated. A facility is normally characterized as a wet pond if shallow zones (<0.5 m deep) comprise less than 20% of its surface area, while a facility is normally characterized as a wetland if shallow zones (<0.5 m deep) make up more than 70 % of its volume.

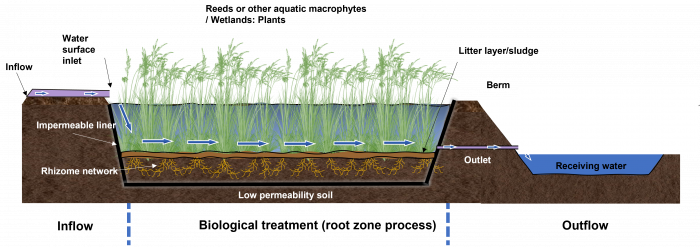

- Sub surface flow systems provide generally lower health and safety risks and are sometimes employed to handle stormwater in combination with another wastewater stream. In horizontal sub-surface flow wetlands, water flows horizontally through a media bed, while in vertical sub-surface flow wetlands, water is introduced at the surface and percolates vertically through the media.

| Horizontal sub-surface flow | Vertical sub-surface flow |

|---|---|

|

|

Pros

|

Pros

|

Cons

|

Cons

|

Design[edit]

Sizing free-water[edit]

Design recommendations differ between SWM ponds and constructed wetlands. Below are the sizing recommendations for free-water surface flow wetlands.

| Element | Design Objective | Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Drainage Area | Sustaining vegetation, volumetric turnover | 5 Ha (≥10 Ha preferred) |

| Treatment Volume | Provision of appropriate level of protection | See below |

| Active Storage | Detention | Suspended solids settling 24 hrs (12 hrs if in conflict with min. orifice size) |

| Forebay | Pre-treatment |

|

| Length-to-Width Ratio | Maximize flow path and minimize short-circuiting potential |

|

| Permanent pool depth | Vegetation requirements, rapid settling | The average permanent pool depth should range from 150 mm to 300 mm |

| Active storage depth | Storage/flow control, sustaining vegetation | Maximum 1.0 m for storms < 10 year event |

| Side slopes (See also berms) | Safety |

|

| Inlet | Avoid clogging/freezing |

|

| Outlet (See also flow control) | Avoid clogging/freezing |

|

| Maintenance access | Access for backhoes or dredging equipment |

|

| Buffer | Safety | Minimum 7.5 m above maximum water quality/erosion control water level |

A larger storage volume (up to 140 m3/ha) is recommended for constructed wetlands designed to enhance suspended solid removal and treat runoff from catchments with a high impervious cover. Conversely, constructed wetlands designed for basic treatment and low impervious cover can be have lower storage volumes (minimum of 60 m3/ha). The table below shows recommended storage volumes for constructed wetlands, depending on level of protection and impervious cover. For comparison, the recommended storage volume for wet ponds is 60 - 250 m3/ha.

| Performance level | Storage volume (m3/Ha) required according to catchment impervious cover | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35% | 55% | 70% | 85% | |

| 80 % TSS removal | 80 | 105 | 120 | 140 |

| 70 % TSS removal | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 |

| 60 % TSS removal | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

Modeling sub-surface[edit]

SubWet 2.0 is a modeling tool for sub-surface flow wetlands (both 100% constructed and naturalized/adapted). It can be used to simulate removal of nitrogen (including nitrogen in ammonia, nitrate and organic matter), phosphorus and BOD5 in mg/l and the corresponding removal efficiencies (in %). Although the model has been calibrated already with data from cold and warm climates, users can further calibrate and validate it using local data observations.

Materials[edit]

- For planting recommendations, see Wetlands: Plants

Performance[edit]

Relative to a wet pond, a constructed wetland may offer added pollutant removal benefits due to enhanced biological uptake and the filtration effects of the vegetation. Early stage wetlands readily sorb phosphorus onto substrates and sediments. Phosphorus removal in wetland systems is usually carried out by incorporating alum sedimentation ponds or sand filters as cells of the system, and/or by polishing wetland effluent in an iron-dosed mechanical filter.<ref name="JW">

Freezing temperatures in winter and early spring can reduce treatment if the wetland either freezes solid or a cover of ice prevents the water from entering the wetland. If under-ice water becomes confined, water velocities may increase, thereby reducing contact times[6]. Runoff in excess of maximum design flows should be diverted around the wetland to avoid excessive flows through the wetland.

STEP (under previous name SWAMP) conducted their own research into the performance of stormwater wetlands, the project page and report can be viewed here.

Central Lake Ontario Conservation Authority have been undertaking a coastal wetland monitoring project across Durham region, see here.

Inspections and Maintenance[edit]

Gallery[edit]

Emergent wetland vegetation supported by stormwater runoff at Kino Environmental Restoration Project. Photo by Matthew Grabau, US Fish and Wildlife Service

Azalea Park, Charlottesville VA - "This side of the park, formerly located along a runoff channel that led into Moore's Creek, has been converted into a wetland which supports a surprising amount of insect and amphibian life." -Credit and Photo: Scott Clark (certhia on Flickr).

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. 2017. A Wetland Conservation Strategy for Ontario 2017–2030. https://www.ontario.ca/page/wetland-conservation-strategy

- ↑ Toronto and Region Conservation Authority. 2025. Wetlands. https://trca.ca/conservation/restoration/wetlands/#:~:text=Increased%20biodiversity,as%20bird%20watching%20and%20fishing

- ↑ Bendoricchio, G., L. Dal Cin, and J. Persson. 2000. Guidelines for free water surface wetland design. EcoSys Bd 8: 51–91. http://www.pixelrauschen.de/wet/design.pdf

- ↑ Kennedy, G., and T. Mayer. 2002. Natural and Constructed Wetlands in Canada: An Overview. Water Qual. Res. J. Canada 37(2): 295–325. doi: 10.2166/wqrj.2002.020.

- ↑ Grant, N., M. Moodie, and C. Weedon. 2000. Sewage Treatment Solutions. p. 35–67. In Sewage Solutions: Answering the Call of Nature. Centre for Alternative Technology Publications.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 United States Environmental Protection Agency. 1995. A handbook of constructed wetlands: A guide to creating wetlands for agricultural wastewater, domestic wastewater, coal mine drainage and stormwater.

- ↑ Jacques Whitford Consultants, 2008. Constructed and engineered wetlands. p. 1-21

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA), and CH2M Hill Canada. 2018. Inspection and Maintenance Guide for Stormwater Management Ponds and Constructed Wetlands (T van Seters, L Rocha, and K Delidjakovva, Eds.). https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2018/04/SWMFG2016_Guide_April-2018.pdf