Difference between revisions of "Flood mitigation"

Tvanseters (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (8 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{TOClimit|2}} | {{TOClimit|2}} | ||

==Pluvial (Surface) flooding== | ==Pluvial (Surface) flooding== | ||

| − | Pluvial flooding occurs when | + | Pluvial flooding occurs when larger storms exceed the capacity of the urban drainage system to convey water, resulting in flooding of some low-lying areas. This may result in traffic interruption, economic loss, infrastructure damage, basement flooding and other undesirable consequences. As the climate changes, the incidence of extreme weather events in Ontario is expected to increase, causing urban drainage system capacity to be exceeded more frequently. This will be particularly severe in older areas where the minor system was not designed to today’s standards and/or major drainage system pathways have been altered or do not exist. |

| − | + | ||

| + | LIDs are well suited to address localized flooding because they can be shoehorned into smaller areas that may have increased flood risk. Runoff reduction and temporary detention are the primary means by which LIDs can reduce flooding at the scale of urban drainage systems. Kim & Han (2008)<ref>Kim, Y., & Han, M. (2008). Rainwater storage tank as a remedy for a local urban flood control. Water Science and Technology: Water Supply, 8(1), 31-36.</ref> and Han & Mun (2011)<ref>Han, M. Y., & Mun, J. S. (2011). Operational data of the Star City rainwater harvesting system and its role as a climate change adaptation and a social influence. Water Science and Technology, 63(12), 2796-2801.</ref> conducted studies in Seoul, South Korea, to assess the extent to which the installation of rainwater harvesting cisterns could help mitigate existing urban flooding problems without expanding the capacity of the existing urban drainage system. System operational data showed that 29 mm of rainwater storage per square meter of impervious area (3000 m<sup>3</sup> cistern in this instance) provided sufficient storage for a one in 50 year period storm without the need to upgrade downstream sewers designed to 10 year storm capacity. Stormwater chambers, infiltration chambers, bioretention and other LID systems designed with large volumes of temporary storage could have similar benefits, while also reducing runoff volumes and providing other co-benefits (see section below on ‘designing for flood resilience’). | ||

==Riverine Flooding== | ==Riverine Flooding== | ||

| − | |||

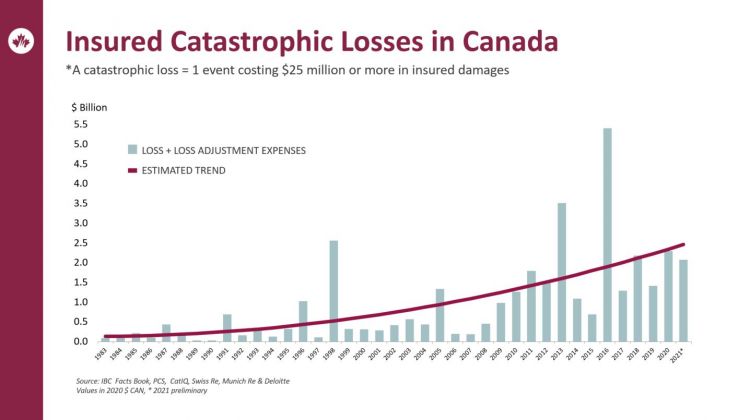

| − | '' | + | [[File:2022-01-18-severe-weather-2021-21-billion-damage-image2.jpeg|thumb|750px|The above chart shows insurable losses each year caused by natural disasters, the most costly of these being flooding, as reported by the Insurance Bureau of Canada in 2022. ''“In today's world of extreme weather events, the new normal for yearly insured catastrophic losses in Canada has become $2 billion, most of it due to water-related damage. Compare this to the period between 1983 and 2008, when Canadian insurers averaged only $422 million a year in severe weather-related losses."'' (IBC, 2022).<ref>Insurance Bureau of Canada (IBC). 2022. Severe Weather in 2021 Caused $2.1 Billion in Insured Damage." News & Insights. Accessed: https://www.ibc.ca/news-insights/news/severe-weather-in-2021-caused-2-1-billion-in-insured-damage</ref>.]] |

| − | + | Riverine flooding occurs when rivers and streams exceed the capacity of their channels to convey flows, resulting in water overtopping the banks and flowing into adjacent areas. In urban areas, this typically occurs where there has been an increase in upstream impervious cover that is not adequately mitigated by stormwater management practices. | |

| + | <br> | ||

| − | + | ''“Hydrological changes associated with urbanisation are increased storm runoff volumes and peak flows (Qp), faster flow velocities and shorter time of concentrations. A reduction in infiltration generally leads to less groundwater recharge and baseflow.The flashy response results in tremendous stresses for the urban stream and downstream receiving areas (Walsh et al., 2005)."'' | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Catastrophic losses from flooding have been steadily rising in Canada over the last two decades. The most common stormwater practices for mitigating riverine flooding are wet ponds and dry ponds, typically located at the end of the urban drainage system near streams. LIDs are traditionally designed to manage more frequent and lower magnitude rain events. However, as mentioned above, larger storm chambers, trenches and even bioretention can be designed with large temporary storage volumes to provide flood control functions similar to wet or dry ponds. | |

| − | + | The most common stormwater practices for mitigating riverine flooding are wet ponds and dry ponds, typically located at the end of the urban drainage system near streams. LIDs are traditionally designed to manage more frequent and lower magnitude rain events. However, as mentioned above, larger storm chambers, [[infiltration trench|trenches]] and even [[bioretention]] can be designed with large temporary storage volumes to provide flood control functions similar to wet or [[dry ponds]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Hydrological model | + | In order to protect downstream properties from flooding due to upstream development, Conservation Authorities establish flood control for future SWM planning through regularly updated of Hydrologic Studies and Subwatershed-level Stormwater Management Studies that characterize flood flow rates, define the location and extent of Flood Damage Centers and assess the potential impact of further urbanization. |

| + | |||

| + | Infiltration facilities and low impact development practices (such as [[bioretention]] and [[rainwater harvesting]]) are typically designed to manage more frequent and lower magnitude rainfall events. However, should these practices be designed for year round functionality, with sufficient flood storage capacity, the volume reductions associated with these practices will be recognized where the local municipality has endorsed the use of these practices and has considered long term operations and maintenance. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Modelling Flood Mitigation Potential of Conventional LIDs== | ||

| + | |||

| + | TRCA conducted [[modeling]] to evaluate the capacity of different stormwater management measures (LID and Ponds) to mitigate impacts of development on the peak flow and runoff volume. A sub-catchment in Humber River was selected that has an area of 35.7 ha. The existing land use in the sub-catchment is agriculture and the proposed future land use is employment land with 91% total imperviousness. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hydrological model runs were carried out by integrating different stormwater management measures (LID and SWM Pond) for 2-year and 100-year 6-hr AES design storms. | ||

Scenarios evaluated include: | Scenarios evaluated include: | ||

| Line 35: | Line 39: | ||

*For 50 and 100 year design storms it reduces only 4% and 1% respectively. | *For 50 and 100 year design storms it reduces only 4% and 1% respectively. | ||

| − | This shows that LID will not reduce | + | This shows that LID designed for frequent flows will not significantly reduce the post-development peak flows generated from major storms. In order to meet flood control requirements, traditional LID need to be augmented by some flood storage measures such as [[dry ponds]] or [[infiltration chambers|underground storage]]. As noted below, LIDs can be designed with increased temporary storage to increase detention times. This allows them to function more like underground end-of-pipe facilities (see Honda case study below) |

| − | In order to meet flood control requirements, LID need to be augmented by some flood storage measures such as [[dry ponds]] or [[infiltration chambers|underground storage]]. | ||

===Runoff Volume=== | ===Runoff Volume=== | ||

*The 25 mm on-site retention using LID measures can reduce post-development runoff volume generated from 2 to 5 year design storms by over 52 %, | *The 25 mm on-site retention using LID measures can reduce post-development runoff volume generated from 2 to 5 year design storms by over 52 %, | ||

| − | *For 50 | + | *For 50 and 100 year design storms, runoff volumes are reduced by 33% and 30%, respectively |

| + | |||

| + | This shows that the post-development runoff volume generated from major storms conveyed to receiving features can be reduced considerably by implementing LID designed to retain 25 mm. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==LID Design for Flood Control== | ||

| + | |||

| + | A large number of studies have shown the beneficial effect of LID on reducing peak flows for more frequent events. They do this by detaining flows and releasing them over longer time periods (see figure below). However, as discussed in the previous section, larger events overwhelm the capacity of these LID practices to provide significant flood mitigation because most practices are designed with overflows that rapidly discharge incoming runoff to storm sewers once the design capacity of the practice has been exceeded. | ||

| + | |||

| − | |||

==Literature Review== | ==Literature Review== | ||

| Line 101: | Line 110: | ||

*Inlet design to accept the minor and major system | *Inlet design to accept the minor and major system | ||

*How to incorporate emergency overflow structures into the design? | *How to incorporate emergency overflow structures into the design? | ||

| − | *What features can be incorporated | + | *What features can be incorporated to adjust the infrastructure? |

Check for related content on [[Peak flow]] | Check for related content on [[Peak flow]] | ||

Latest revision as of 16:07, 3 April 2024

Pluvial (Surface) flooding[edit]

Pluvial flooding occurs when larger storms exceed the capacity of the urban drainage system to convey water, resulting in flooding of some low-lying areas. This may result in traffic interruption, economic loss, infrastructure damage, basement flooding and other undesirable consequences. As the climate changes, the incidence of extreme weather events in Ontario is expected to increase, causing urban drainage system capacity to be exceeded more frequently. This will be particularly severe in older areas where the minor system was not designed to today’s standards and/or major drainage system pathways have been altered or do not exist.

LIDs are well suited to address localized flooding because they can be shoehorned into smaller areas that may have increased flood risk. Runoff reduction and temporary detention are the primary means by which LIDs can reduce flooding at the scale of urban drainage systems. Kim & Han (2008)[1] and Han & Mun (2011)[2] conducted studies in Seoul, South Korea, to assess the extent to which the installation of rainwater harvesting cisterns could help mitigate existing urban flooding problems without expanding the capacity of the existing urban drainage system. System operational data showed that 29 mm of rainwater storage per square meter of impervious area (3000 m3 cistern in this instance) provided sufficient storage for a one in 50 year period storm without the need to upgrade downstream sewers designed to 10 year storm capacity. Stormwater chambers, infiltration chambers, bioretention and other LID systems designed with large volumes of temporary storage could have similar benefits, while also reducing runoff volumes and providing other co-benefits (see section below on ‘designing for flood resilience’).

Riverine Flooding[edit]

Riverine flooding occurs when rivers and streams exceed the capacity of their channels to convey flows, resulting in water overtopping the banks and flowing into adjacent areas. In urban areas, this typically occurs where there has been an increase in upstream impervious cover that is not adequately mitigated by stormwater management practices.

“Hydrological changes associated with urbanisation are increased storm runoff volumes and peak flows (Qp), faster flow velocities and shorter time of concentrations. A reduction in infiltration generally leads to less groundwater recharge and baseflow.The flashy response results in tremendous stresses for the urban stream and downstream receiving areas (Walsh et al., 2005)."

Catastrophic losses from flooding have been steadily rising in Canada over the last two decades. The most common stormwater practices for mitigating riverine flooding are wet ponds and dry ponds, typically located at the end of the urban drainage system near streams. LIDs are traditionally designed to manage more frequent and lower magnitude rain events. However, as mentioned above, larger storm chambers, trenches and even bioretention can be designed with large temporary storage volumes to provide flood control functions similar to wet or dry ponds.

The most common stormwater practices for mitigating riverine flooding are wet ponds and dry ponds, typically located at the end of the urban drainage system near streams. LIDs are traditionally designed to manage more frequent and lower magnitude rain events. However, as mentioned above, larger storm chambers, trenches and even bioretention can be designed with large temporary storage volumes to provide flood control functions similar to wet or dry ponds.

In order to protect downstream properties from flooding due to upstream development, Conservation Authorities establish flood control for future SWM planning through regularly updated of Hydrologic Studies and Subwatershed-level Stormwater Management Studies that characterize flood flow rates, define the location and extent of Flood Damage Centers and assess the potential impact of further urbanization.

Infiltration facilities and low impact development practices (such as bioretention and rainwater harvesting) are typically designed to manage more frequent and lower magnitude rainfall events. However, should these practices be designed for year round functionality, with sufficient flood storage capacity, the volume reductions associated with these practices will be recognized where the local municipality has endorsed the use of these practices and has considered long term operations and maintenance.

Modelling Flood Mitigation Potential of Conventional LIDs[edit]

TRCA conducted modeling to evaluate the capacity of different stormwater management measures (LID and Ponds) to mitigate impacts of development on the peak flow and runoff volume. A sub-catchment in Humber River was selected that has an area of 35.7 ha. The existing land use in the sub-catchment is agriculture and the proposed future land use is employment land with 91% total imperviousness.

Hydrological model runs were carried out by integrating different stormwater management measures (LID and SWM Pond) for 2-year and 100-year 6-hr AES design storms.

Scenarios evaluated include:

- LID measures that provide 25 mm on-site retention

- SWM pond to control post-development peak flows to pre-development peak flows.

- Combination of scenario 1 and scenario 2

Runoff volume and peak flow reductions were calculated:

Peak Flow[edit]

- The 25 mm on-site retention using LID measures reduced post-development peak flows generated from 2 to 5 year design storms by over 26%,

- For 50 and 100 year design storms it reduces only 4% and 1% respectively.

This shows that LID designed for frequent flows will not significantly reduce the post-development peak flows generated from major storms. In order to meet flood control requirements, traditional LID need to be augmented by some flood storage measures such as dry ponds or underground storage. As noted below, LIDs can be designed with increased temporary storage to increase detention times. This allows them to function more like underground end-of-pipe facilities (see Honda case study below)

Runoff Volume[edit]

- The 25 mm on-site retention using LID measures can reduce post-development runoff volume generated from 2 to 5 year design storms by over 52 %,

- For 50 and 100 year design storms, runoff volumes are reduced by 33% and 30%, respectively

This shows that the post-development runoff volume generated from major storms conveyed to receiving features can be reduced considerably by implementing LID designed to retain 25 mm.

LID Design for Flood Control[edit]

A large number of studies have shown the beneficial effect of LID on reducing peak flows for more frequent events. They do this by detaining flows and releasing them over longer time periods (see figure below). However, as discussed in the previous section, larger events overwhelm the capacity of these LID practices to provide significant flood mitigation because most practices are designed with overflows that rapidly discharge incoming runoff to storm sewers once the design capacity of the practice has been exceeded.

Literature Review[edit]

Review examples of where LID practices with quantity control components have been used for achieving flood control

Example 1: Costco Distribution Centre

Costco Distribution Centre located within Block 59, Vaughan. The site has 26.4 ha and the land use is commercial site with an average site imperviousness of approximately 90%;

Stormwater Management Criteria

- Quantity Control – meet Humber River Unit Release Rates;

- Quality Control – 80% TSS Removal;

- Water Balance – Best Efforts to match post to pre;

- Erosion control, 25mm erosion storm released over 72 hours, on-site retention of the first 5mm of rainfall

Stormwater Management Strategy

- A series of sub-surface infiltration chambers providing on-site retention/infiltration of the 5mm storm, water balance to reduce runoff volumes, and storage of the 100-year storm;

- Quality treatment provided using an oil/grit separator immediately upstream of each of the infiltration chambers, filtration through the infiltration chamber, and finally a stormwater management facility provided prior to discharging from the site.

- Final erosion control provided within the stormwater management facility, controlling release rates to maintain the existing condition erosion exceedance values.

- Final design required both LIDs to reduce the overall runoff volumes, but also sub-surface storage chambers to provide quantity control for rare storm events up to the 100-year design storm. Due to large area required for truck parking, limited opportunities for more landscaping to promote evapotranspiration, runoff volumes increased beyond ability of LIDs to negate the need for quantity control.

Example 2. West Gormley, Town of Richmond Hill

Residential development consisting of low and medium density land-use is implemented on the site. Average site imperviousness is approximately 60%;

Stormwater Management Criteria

- Quantity Control – Rouge River – match post development peak flow rates to pre-development;

- Quality Control – 80% TSS Removal;

- Water Balance –Match post development water budget to pre-development;

- Erosion Control – Southern portion of site discharging to a natural dry valley feature. Feature and contributing drainage area consists of very sandy soil, producing no runoff until a greater than 25-year storm event.

- Therefore, development discharging to dry valley needed to match runoff volumes, or have no runoff from development area for storms less than 25-year design storm.

Stormwater Management Strategy

- Use a combination of increased topsoil depths, perforated storm sewers, stormwater management facility, and an infiltration facility to provide quality, quantity, and reduce runoff volumes to match pre-development.

- Even with favorable soils and maximum use of infiltration techniques, site still requires quantity control storage for large storm events.

Example 3: 3775-4005 Dundas St West (includes 2-6 Humber Hill Ave), Toronto

The size of the site is 0.53 ha. The site currently developed as commercial and residential. Proposed high rise (11-storeys) residential building with 3 levels of underground parking Proposed average site imperviousness is 90% (excluding uncontrolled buffer area 0.22 ha)

Stormwater Management Criteria

- Quantity Control – not requirement as drains to Lower Humber River

- Quality Control – 80% TSS Removal

- Water balance/Erosion Control – Retention of 5 mm event on-site

Stormwater Strategy

- Large portion of the roof proposed as green roof and cistern proposed in underground parking to capture remaining volume to meet 5 mm target. Water to be used for irrigation and carwash stations.

- Quality target achieved as majority of site is ‘clean’ roof water or directed to pervious area. Underground storage tank provided to satisfy municipal release rates to receiving storm sewer system.

- Final design required both LIDs to reduce the overall runoff volumes, but also sub-surface storage chambers to provide quantity control to meet municipal requirements.

- Due to underground parking limited opportunities for infiltration LIDs but used green roof to promote evapotranspiration, and cistern to reduce runoff volumes.

Data Analysis/Modelling[edit]

- Suggest detailed modelling to evaluate how source and conveyance controls could provide a flood control function

- Fieldwork

- Visit sites to record information/interview designer/landowner

- Technical Input/Design Considerations

- If flood control is your goal how does that impact other performance measures?

- How do other combinations of infrastructure impact effectiveness? For example, underdrains, ponding overflow drains, and inlets/outlets may significantly reduce the effectiveness of the practice to retain runoff and also increase costs?

- How would we have designed Elm Drive differently?

- Reducing the potential to mobilize and wash out soil media and erode the practice (this was a big concern raised by Mississauga with the LRT)

- Inlet design to accept the minor and major system

- How to incorporate emergency overflow structures into the design?

- What features can be incorporated to adjust the infrastructure?

Check for related content on Peak flow

- ↑ Kim, Y., & Han, M. (2008). Rainwater storage tank as a remedy for a local urban flood control. Water Science and Technology: Water Supply, 8(1), 31-36.

- ↑ Han, M. Y., & Mun, J. S. (2011). Operational data of the Star City rainwater harvesting system and its role as a climate change adaptation and a social influence. Water Science and Technology, 63(12), 2796-2801.

- ↑ Insurance Bureau of Canada (IBC). 2022. Severe Weather in 2021 Caused $2.1 Billion in Insured Damage." News & Insights. Accessed: https://www.ibc.ca/news-insights/news/severe-weather-in-2021-caused-2-1-billion-in-insured-damage