Integrated water management

Collaboration leads to innovation "An integrated design process (IDP) involves a holistic approach to high performance building design and construction. It relies upon every member of the project team sharing a vision of sustainability, and working collaboratively to implement sustainability goals. This process enables the team to optimize systems, reduce operating and maintenance costs and minimize the need for incremental capital. IDP has been shown to produce more significant results than investing in capital equipment upgrades at later stages."[1]

The Ryerson Urban Water group has developed a free modeling tool for neighbourhood scale integrated water resources evaluation. View the tool at http://iwret.ryerson.ca/.

Introduction[edit]

Historic approaches to stormwater management – which initially focused on conveyance, followed by flood control and eventually some aspects of water quality – failed to address the full range of water resources related issues associated with stormwater runoff. A holistic, integrated approach to stormwater planning and management is required Tto adequately deal with changes to the volume, rate and timing of runoff, and to design source, conveyance and end-of-pipe controls capable of satisfying groundwater recharge, water quality and variable environmental flow targets. To achieve this, a robust, interdisciplinary team consisting of infrastructure, water resources engineers, geomorphologists, hydrogeologists, ecologists, fisheries biologists, landscape architects and other disciplines must come together in order to define key targets and resource management goals underpinning the one water approach.

The one water approach[edit]

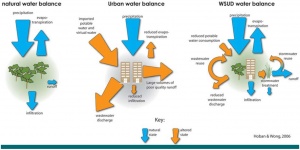

The one water approach is predicated on the fact that drinking water, wastewater and stormwater systems share intrinsic connections, and that none of these systems can be managed in isolation from one another. The ultimate goal of the one water approach is to mimic the natural hydrologic cycle. The figure to the right illustrates how different hydrologic components are altered as progressive urbanization occurs.

In the natural hydrologic cycle, evapotranspiration and infiltration are the dominant pathways within the hydrologic cycle, and as a result this condition produces relatively little runoff. In urban environments, a rise in impervious surfaces coupled with a net loss of vegetation (interception storage and evapotranspiration) and the implementation of a dense storm sewer network significantly reduces evapotranspiration and infiltration processes and produce large amounts of urban runoff in much shorter timeframes. Within the urban water balance, piped and/or pumped potable water and wastewater discharges are also represented within the cycle.

Water resource management in Ontario[edit]

In Ontario, water management and planning is consistent with municipal land-use planning and is largely done as part of the master planning, watershed planning, and environmental planning process, which are the responsibilities of municipalities and conservation authorities. In order to successfully carry out integrated water management in Ontario, the planning process should be undertaken through a collaborative, interdisciplinary process. This will maximize the likelihood that management plans will satisfy the specific needs of the individual parties who are responsible for providing both water services and water management. Successful application of the One Water approach requires that management and planning optimization for drinking water, wastewater and stormwater systems all be carried out at the appropriate scale. For the purposes of safeguarding life and property against the ravages of flooding and degraded water quality, and in order to meet the needs of biotic life support systems, the appropriate scale for management is at the watershed level. Since watershed boundaries transcend municipal boundaries, a spirit of collaboration between neighbouring municipalities is also required. In order to optimize the aforementioned systems, adequate planning surrounding other components is also required.

Key components include:

- Long-term infrastructure master plans

- Asset management plans (for DW, WW and SW infrastructure)

- Financial plans

- Water conservation plans

- Risk assessments for both existing and anticipated future risks (including the growing risks posed by climate change), and

- Strategies to maintain and improve water management services.

- ↑ Natural Resources Canada. The integrated design process. http://www.nrcan.gc.ca/energy/efficiency/buildings/eenb/integrated-design-process/4047. Accessed September 12, 2017.