Source Water Protection

Overview[edit]

In response to the Walkerton tragedy in May of 2000, where 2,500 residents of the town fell ill due to ingesting high levels of E.coli bacteria and 7 individuals died due to poor monitoring and maintenance of the drinking water system, the Province of Ontario enacted new rules and safeguards to ensure drinking water sources are adequately protected. Following an inquiry into the Walkerton tragedy, Justice O'Connor made over 120 recommendations to better protect the province's drinking water, which have formed the foundation of the province's source water protection framework. The first of the Walkerton Inquiry recommendations was that drinking water should be protected by developing watershed-based source water protection plans.

Source Water Protection In Ontario[edit]

The Clean Water Act requires municipalities to protect their drinking water sources and supplies through prevention, by developing collaborative, watershed-based source water protection plans.[2]

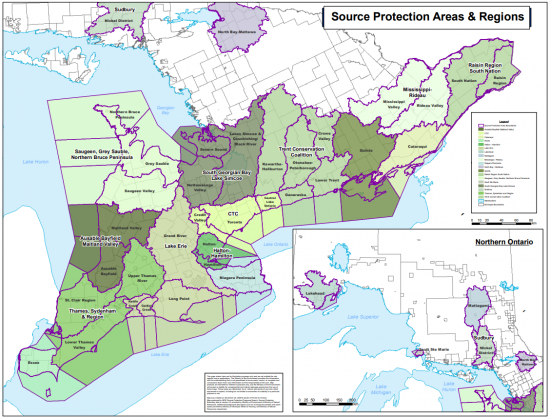

The Clean Water Act defines source water protection areas and source water protection regions as follows:

- Source Protection Region (SPR): Encompass one or more source protection areas (e.g., Credit Valley-Toronto and Region-Central Lake Ontario, or "CTC" Region).

- Source Protection Area (SPA): Smaller geographic areas generally based on the watershed boundaries of Ontario's 36 Conservation Authorities

Under the Clean Water Act, local multi-stakeholder source water protection committees have been established for each source water protection area or region. Each committee is comprised of the region's leading researchers, professionals and technical experts that work together to identify current and potential future threats to municipal drinking water sources. Organizations typically represented on source water protection committees include, but are not limited to the following:

- Conservation authorities;

- Municipalities;

- Local public health boards;

- Indigenous groups, committees and governments;

- Local businesses; and

- Province of Ontario.

The source water protection committee may use a variety of approaches to protect drinking water sources, which can include:

- Prescribed policy instruments (existing provincial approvals such as Environmental Compliance Approvals and Permits To Take Water);

- Requiring landowners to prepare a formal risk management plan (negotiated individually);

- Specified land use planning policies;

- Prohibition of activities within protection areas or zones that may prove detrimental to drinking water sources; and/or,

- Outreach and education activities (webinars, town meetings, pamphlets, online education hubs) (CTC SPR, 2019)[4]

Under the Clean Water Act, 2006 a total of 19 source protection regions and areas have been established across the province (see map above). Each have their own local multi-stakeholder source protection committee, and have developed 38 watershed-based source protection plans. These plans identify various actions to protect over 450 municipal drinking water systems, servicing 95% of Ontario's population. (Government of Ontario, 2021)[2].

Source Protection Plans[edit]

A source protection plan (SPP) contains policies developed by the source water protection committee aimed at protecting existing and future sources of municipal drinking water from significant threats to both quality and quantity of the resources. Land use activities that represent threats to drinking water sources have been identified and categorized as significant when located within highly vulnerable areas or zones, such as wellhead protection areas (WHPAs) for municipal groundwater wells, intake protection zones (IPZs) for surface water sources, and significant groundwater recharge areas (SGRAs).

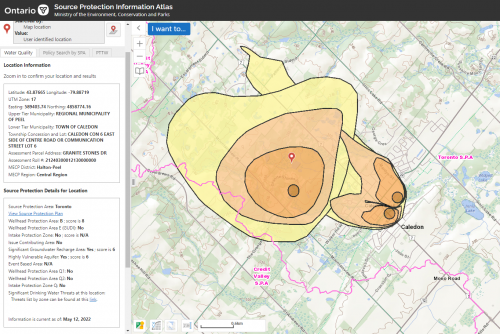

An important first step for designers and approvers of all stormwater management systems in Ontario is to determine if land use activities associated with the proposed development represent significant threats to municipal drinking water sources, and what source water protection plan and associated policies apply to the site. The Province of Ontario's Source Water Protection Information Portal provides a convenient means of screening proposals based on threat subcategory and geographic location, and identifying the source protection plan to consult for further guidance and specific policies.

Based on the most current Drinking Water Threats and Circumstances database tool, development of stormwater treatment and infiltration facilities, outfalls and associated infrastructure, whether servicing an industrial/commercial, residential/institutional or rural development, may represent significant threats to drinking water sources when proposed within certain WHPA and IPZ areas and may need to be located outside of highly vulnerable areas or zones. Proposed developments that include creation of paved areas that will receive road salt applications during winter may also represent a significant threat to drinking water quality in highly vulnerable areas or where source water quality issues already exist (i.e., issue-contributing areas). Furthermore, if the proposed development involves creation of impermeable surfaces to the extent that it will significantly reduce recharge to an aquifer, stormwater infiltration facilities may need to be included.

The Province of Ontario's on-line Source Protection Information Atlas can be used to determine what source water protection area or region a proposed development site is located within, and if it falls within a vulnerable area where source water protection policies would apply. If the proposed development site is located in a vulnerable area or zone, the current source water protection plan in place for the location should be checked and source water protection committee representative should be consulted to determine what policies apply or what protective measures will be required.

Once you know what source water protection area or region a proposed development site is located in, and if it includes vulnerable areas or zones, the alphabetical list below of links to dedicated websites of each source water protection areas and region in Ontario can be used to access existing source protection plan documents, recent assessment reports, committee member contacts and other helpful resources:

- Ausable Bayfield Maitland Valley Source Protection Region

- Cataraqui Source Protection Area

- CTC Source Protection Region

- Essex Region Source Protection Area

- Greater Sudbury Source Protection Area

- Halton-Hamilton Source Protection Region

- Lake Erie Source Protection Region

- Lakehead Source Protection Area

- Mattagami Region Source Protection Area

- Mississippi-Rideau Source protection Region

- Niagara Peninsula Source Protection Area

- North Bay-Mattawa Source Protection Area

- Quinte Region Source Protection Area

- Raisin-South Nation Source Protection Region

- Saugeen, Grey Sauble, Northern Bruce Peninsula Source Protection Region

- Sault Ste. Marie Region Source Protection Area

- South Georgian Bay Lake Simcoe Source Protection Region

- Thames-Sydenham Source Protection Region

- Trent Conservation Coalition Source Protection Region

Source Protection Assessment Reports[edit]

Each of the 19 aforementioned SPRs & SPAs has an Assessment Report that acts as a 'living technical document' for that given region. The Assessment report includes:

- Recent research findings and scientific information regarding source water protection;

- A brief overview of each impacted watershed within the SPR/SPA;

- Provides a water budget (which is a way to measure the amount of freshwater water enters, is stored, and leaves a watershed);

- Identifies vulnerable areas near key freshwater sources (municipal wells and intakes);

- Identifies the number of significant threats (agricultural practices, sewage sources, fertilizers, etc.) to water quality near wells and intakes; and,

- Identifies areas that could have varied threat levels (low, moderate, high) (CTC SPR, 2019)[4]

Planning Considerations[edit]

When planning any new development within a SPR/SPA its important to follow the following four (4) major steps before moving forward.

1) Identify and Map Vulnerable Areas[edit]

The two major areas of significance that are vulnerable to water/groundwater pollution threats are called Wellhead Protection Areas (WHPAs) and Intake Protection Zones (IPZs). New development must note if any of their proposed activities or future actions will cause potential negative impacts on these important municipal sources of freshwater.

Wellhead Protection Areas (WHPAs)[edit]

A Wellhead Protection Area (WHPA) is an area located on the ground surface that denotes a specific zone within a known aquifer where fresh groundwater flows to a pumping well. Any detrimental activities/actions that take place in this zone may contribute to pollutions that can infiltrate into the underlying soil below and in turn contaminate said groundwater source for private and municipal wells alike - hence undertaken in this area may release pollutants that could seep into the soil and contaminate the groundwater used by both domestic and municipals wells. As a result, these areas require high levels of monitoring, protection and enforcement. Accordingly, this area warrants greater protection.

The risk to groundwater quality at the well site is determined by the rate at which a specific pollutant/contaminant can infiltrate and travel to the well and the time it would take to remediate the contaminant from the water supply by trained municipal water operators. If a chemical/contaminant spill were to happen a far distance away from a known well, a follow up assessment will be required, this assessment includes:

- Determining whether the contaminant could reach the well in question and the duration of time it may take to reach it.

- Is the contaminant a human, biological or environmental risk or is it simply an aesthetic nuisance?

- Will the concentration of said contaminant exceed the Canadian Water Quality Guidelines (CWQG) for drinking water standard or the Provincial Water Quality Monitoring Network (PWQMN) standard (i.e chloride levels)?

- Will the current mitigation/treatment protocols currently used be sufficient enough to mitigate/remove the harmful concentration levels of said contaminant from reaching the well?

- If said mitigation/treatment protocol needs to be amended and time allows a mitigation system can be installed to limit the movement of said chemical to the well or the water treatment process at the receiving Water Treatment Plant (WTP) can be modified to sufficiently decrease the concentrations being received

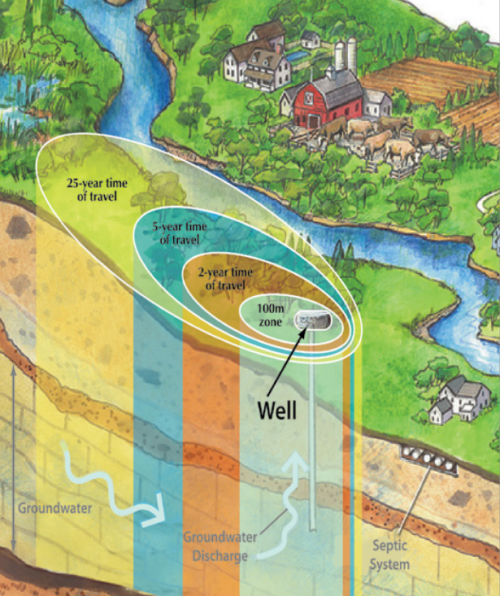

When it comes to WHPAs one size does not fit all, there are multiple zones that extend in an irregular radius around a well to ensure adequate protection of the source water protection area, which is divided into five (5) zones based upon contaminant travel time within groundwater sources:

- WHPA-A – an area of 100 metre radius around the wellhead

- WHPA-B – the zone through which it takes groundwater to travel between two years and the 100 metre distance

- WHPA-C – the zone through which it takes groundwater to travel between five and two years

- WHPA-D – the zone through which it takes groundwater to travel between 25 and five years

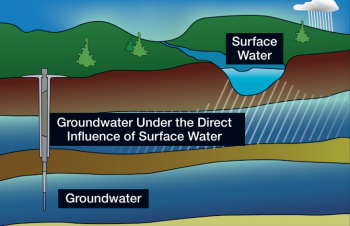

- WHPA-E – the area on ground surface through which surface water flows in two hours to a point close to the well. This wellhead protection area is only delineated when studies have shown that surface water can relatively easily seep through the soil and impact the quality of the water at the well. This situation is known as groundwater under the direct influence of surface water, or a GUDI well

(Halton-Hamilton Source Protection Region, 2010;[6]CTC SPR, 2019[4])

Vulnerability

As mentioned, WHPAs identify an area on the surface that reflects a zone within the underlying aquifer below where groundwater flows to a well. That said, this area is generally not equal to the total contributing water area that drains towards the well over a given duration of time. This contributing area is the location seen on the surface where water can infiltrate into the soil and still reach the well far away. Due to its distance there may be more urbanization within this expanded area and other contributing contaminants that can pollute the groundwater as it flows to the well. This area generally requires the most protection by the associated SPR/SPA, Conservation Authorities located within the area and subsequent municipalities as it is the area/zone most prone to surface contamination (Halton-Hamilton Source Protection Region, 2010[6]).

Vulnerability for source water is simply calculated by:

- Determining the amount of time it takes for water to travel through the "unsaturated zone" above the water table; and,

- Adding that number to the modelled time it takes for groundwater to flow from the water table to the well based on the WHPA zone (EarthFx Incorporated, 2010[8]).

As a result, these surface to well duration periods are categorized as "low" for over 25 years, "medium" for 5 - 25 years, and "high" for 0 - 5 years. These surface to well advection times are categorized as low for over 25 years, medium for 5 to 25 years, and high for 0 to 5 years of travel. After this mapped groundwater vulnerability areas are then overlain on top of current WHPAs A - D to then assign vulnerability scoring between 2 - 10 (lowest - highest vulnerability scores). The location of a potential development site within the WHPA and its vulnerability score are then used to assign the significance of proposed or future potential actions/activities that have been labelled as potential threats to local drinking water sources. These 22 potential threats as laid out by the province can be seen in the table below in this section (Halton-Hamilton Source Protection Region, 2010[6]).

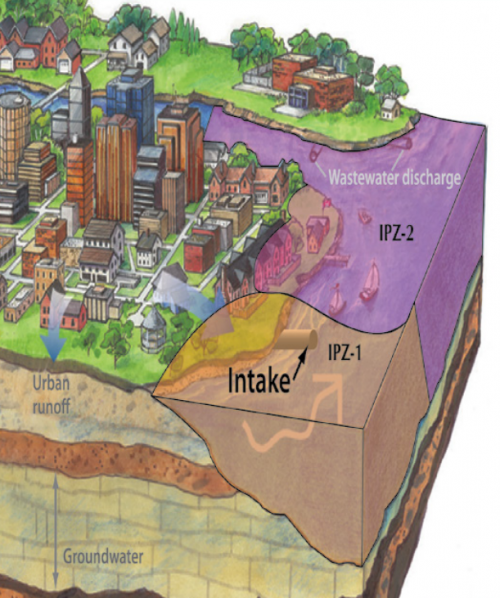

Intake Protection Zones (IPZs)[edit]

An Intake Protection Zone (IPZ) is an area that includes both land and surface water around municipalities' intake pipes that lead to a water treatment plant (WTP) and contributes to the municipalities drinking water system and sources. An IPZ on a map delineates where surface water is originating from and how it end up in the municipal water supply. These zones are determined by how far away they are from the intake location and the time it would take to reach it. The resulting size and shape of each of the three (3) zones of a typical IPZ represents either this set distance around the intake or simply the length of time it would take water and potential contaminants from overland flow to reach the intake.

The 3 zones of IPZ are as follows:

- IPZ‐1: This is the area closest to a municipality's intake pipe and is a set distance which extends one kilometre (Km) upstream and 120 metres onto the shore. IPZ-1 is the most vulnerable to contamination as it is the closest to the intake and allows limited time for dilution to occur to help reduce the concentration of a contaminant released within the zone, this lack of time also doesn't allow municipal water system operators much time to react to this released contamination that is headed towards the municipal intake.

- IPZ‐2: This area is developed by utilizing both hydrodynamic modelling and a time-of-travel calculation within overland pathways (natural and human-made - i.e. rivers, creeks, swales, storm sewers, etc.) that ultimately lead to and discharge near the municipalities intake(s). Includes both the on and offshore areas where overland flowing water that may be polluted with a concentration of a given number of contaminants would be able to reach the municipal intake within approximately two (2) hours. The 2 hour mark is set as the minimum amount of time to allow municipal water system operators to address a potential contamination concern.

- IPZ‐3: This area lies outside of IPZ-1 and IPZ-2 and as such contaminants likely could only reach the intake pipe during and/or after a major rainfall/storm event. The size and shape of an IPZ-3 zone is based on associated lakes, streams and other humanmade conveyances that could contribute excess overland flow during an event.

(Halton-Hamilton Source Protection Region, 2010[9]; Cataraqui Source Protection Area, 2022[10])

Vulnerability

The vulnerability of the three IPZs are assigned scores that reflect their susceptibility to allowing contaminants to reach the municipal intake zone and is determined by local knowledge and technical input from industry experts, as well as judgment from the SPA/SPZ committee members.

The source vulnerability scores for IPZ-1 and IPZ-2 is based on multiplying the following factors:

- Distance of the intake from shore/boundary

- the depth of the intake from surface water interaction

- historical water quality conditions and previous incidents/concerns at the intake in questions

hydrological and hydrogeological conditions of the surrounding area

- IPZ-1, due to its close proximity to the intake is set at the maximum vulnerability score value

- IPZ-2, considers the above characteristics along with the percentage of its area that is landcover

- It also considers land characteristics of this land area (soil permeability, slope and direction, [Soil groups|soil types], vegetation coverage, etc.

- IPZ-3 is not provided a vulnerability score due to its setback distance away from intakes. It's perimeter is designated based on nearby lakes and streams that contribute overland flow to the intake

(Halton-Hamilton Source Protection Region, 2010[9]; Cataraqui Source Protection Area, 2022[10])

Vulnerability for source water is simply calculated by:

- Determining the amount of time it takes for water to travel through the "unsaturated zone" above the water table; and,

- Adding that number to the modelled time it takes for groundwater to flow from the water table to the well based on the WHPA zone (EarthFx Incorporated, 2010[11]).

2) Identify Threats[edit]

There are currently 22 listed "threats" that are outlined in the Clean Water Act, 2006. Please see the table below for further details (Government of Ontario, 2021[12]):

Threat Type

|

Threat Number & Description

|

|---|---|

| Agricultural | |

| 1. The application of agricultural source material to land | |

| 2. The storage of agricultural source material. | |

| 3. The management of agricultural source material. | |

| 4. The use of land as livestock grazing or pasturing land, an outdoor confinement area or a farm-animal yard. | |

| Residential/Commercial | |

| 5. The application of non-agricultural source material to land. | |

| 6. The handling and storage of non-agricultural source material. | |

| Sewage & Waste | |

| 7. The establishment, operation or maintenance of a waste disposal site within the meaning of Part V of the Environmental Protection Act. | |

| 8. The establishment, operation or maintenance of a system that collects, stores, transmits, treats or disposes of sewage. | |

| Fertilizer & Pesticides | |

| 9. The application of commercial fertilizer to land. | |

| 10. The handling and storage of commercial fertilizer. | |

| 11. The application of pesticide to land. | |

| 12. The handling and storage of pesticide. | |

| Winter Maintenance / Salt | |

| 13. The application of road salt. | |

| 14. The handling and storage of road salt. | |

| 15. The storage of snow. | |

| Fuel & Chemicals | |

| 16. The handling and storage of fuel. | |

| 17. The handling and storage of a dense non-aqueous phase liquid. | |

| 18. The handling and storage of an organic solvent. | |

| 19. The management of runoff that contains chemicals used in the de-icing of aircraft | |

| 20. The establishment and operation of a liquid hydrocarbon pipeline. O. Reg. 385/08, s. 3; O. Reg. 206/18, s. 1. | |

| Water Extraction | |

| 21. An activity that takes water from an aquifer or a surface water body without returning the water taken to the same aquifer or surface water body. | |

| 22. An activity that reduces the recharge of an aquifer. |

3) Calculate Threat Level[edit]

To calculate your threat level before commencing work there are several steps to take to determine how you can mitigate your impact on the local water supply.

- Find out if you are in a "Vulnerable Area" as listed under the Clean Water Act, 2006. To do this use the Source Protection Information Atlas tool that shows based on your location vulnerability mapping and scores within already established and mapped source protection areas in your area.

- If your development site is in a known vulnerable area, look at the threats table provided above in this section and ensure that you are not conducting any of the 22 listed activities as outlined under Ontario Regulation 287/07 Section 1.1 (1), "Prescribed drinking water threats".

- After referencing the table if you discover that you will (or may) be conducting one or more of the listed activities then continue forward by contacting your local SPR/SPA (their emails and contact information are listed on their associated websites).

- Your SPR/SPA will be able to determine whether the work you are looking to conduct is deemed either a:

You can go into further details learning about the potential risks your work may pose by visiting the MECP's Best practices for source water protection. This webpage set up by the province allows users to still protect freshwater sources and drinking water systems that are not included within an SPP or regulated under the Clean Water Act, 2006. It provides additional information and approaches prospective developers and users can take based upon local soil infiltration rates, groundwater sources in the area, highly vulnerably aquifers, nearby surface water sources, and other potential factors affecting vulnerability.

Below is a table "risk factors" prospective developers (commercial, residential, municipal) should employ that asks eleven (11) questions and a user can rank to determine how at risk a local drinking water source may be given the work they are considering. Anything listed as "High" warrants further information and action to protect the water source (Table adopted from MECP's Best practices for source water protection (MECP, 2022)[15].

Risk questions |

Low Risk |

Medium Risk |

High Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| How many wells or intakes are located in your area? |

None to "a few" |

Several |

Many |

| How deep are the wells and are they drilled or dug? |

Deep, drilled |

Intermediate |

Shallow, dug |

| How deep is the intake and how far is it located from shore? |

Deep, far |

Intermediate |

Shallow, nearshore |

| What is the vulnerability of your area? |

Low vulnerability setting |

Moderate vulnerability setting |

High vulnerability setting |

| How sensitive is the population? |

Healthy adults only |

Typical family or mixed range of ages |

Vulnerable populations like the elderly, youth or infants |

| How many people does the system serve? |

A few |

Some |

Many |

| How often is the system used? |

Occasionally |

Seasonally or part time (work hours) |

Every day and/or is the only source nearby |

| What types of activities are located nearby? |

Residential |

Agricultural |

Industrial or Commercial |

| Any water quality issues? (i.e. algal booms or a boil water advisories, etc.)? |

Confirmed none |

Possible or Unknown |

Confirmed and Present |

| Are you located in an area where there is pressure for growth? Or are there other water supply and demand issues? |

No |

Maybe / Unknown |

Yes |

| Is there oversight of the well(s) or intake(s)? For example, licencing, inspections, testing, compliance, and qualified operators. |

Yes |

Some |

None |

4) Apply Appropriate Policies[edit]

Policies that must be adhered to are based on several factors:

- The activity itself

- The are in which the activity will be taking place

- The vulnerability of the area in question

- The risks associated with the activity (does the activity result in one of the listed 22 risks occurring or potentially occurring)

- Other local factors that can increase the vulnerability to a nearby IPZs or WHPAs

For example, as of December of 2021 the CTC SPR that comprises the regions of Peel, Toronto, and Durham had nearly 130 Source Protection Policies in place within their SPP. These policies address 21 of the 22 types of threats prescribed in O.Reg 287/07 along with two types of local drinking water threats, and include other actions that are considered by the CTC committee as necessary to protect drinking water sources, along with requirements for the need of monitoring being implemented. The CTC SPP also contain policies which require the need for Risk Management Plans (RMPs) dependent on the vulnerability of proposed actions/activities to better manage some drinking water threats (CTC Source Protection Region, 2021)[16]

LID Site Considerations[edit]

| Installation type | Depth to high water or bedrock (m)i | Ratio of impervious drainage area to permeable facility footprint area |

Native soil infiltration rate (mm/hr)ii | Head (m)iii | Space %iv | Slope %v | Applicable in pollution hotspotsvi | Set backs | Karstvii | Drinking Water Source Protection wellhead protection area time of travel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rain barrels | Not a constraint | Not applicable | Not a constraint | 1 | 0 | NA | Yes | None | Yes | None |

| Cisterns | Not a constraint | Not applicable | Not a constraint | 0 | 0 | 0 | Yes | None | Yes | None |

| Roof downspout disconnection | Not a constraint | 4:1 or less | Decompaction if < 15 mm/hr | 0.5 | 5 to 20 | 1 to 5 | Yes | Building Foundation | Yes | None |

| Infiltration trenches or Infiltration chambers | 1 | 5:1 to 20:1 | Not a constraint | 1 to 2 | 0 to 1 | <15 % | Noix | 4m- Building Foundation Underground Utilities, Trees, Drinking Water Wellhead Protection Areas |

No | 2 year - WHPA-B |

| Bioretention | 1 (infiltrating); Not a constraint (non-infiltrating) | 5:1 to 15:1 | Decompaction and underdrain recommended if < 15 mm/hr (infiltrating) |

1 to 2 | 5 to 10 | 0 to 2 | No (infiltrating)ix; Yes (non-infiltrating) | 4m- Building Foundation Underground Utilities, Trees, Drinking Water Wellhead Protection Areas |

No (infiltrating); Yes (non-infiltrating) | 2 year - WHPA-B (infiltrating); None (non-infiltrating) |

| Stormwater planters | Not a constraint | 5:1 | Not a constraint | 1 to 2 | 2 to 5 | 0 to 2 | No (infiltrating)ix; Yes (non-infiltrating) | Building Foundation, Trees | No (infiltrating); Yes (non-infiltrating) | 2 year - WHPA-B (infiltrating); None (non-infiltrating) |

| Vegetated filter strips | Not a constraint | 4:1 or less | Decompaction if < 15 mm/hr | 0 to 1 | 15 to 20 | 1 to 5 | Noix | None | Yes | None |

| Permeable pavements | 1 (infiltrating); Not applicable (non-infiltrating) | 0 to 1:1 | Underdrain recommended if < 15 mm/hr (infiltrating) |

0.5 to 1 | 0 | 1 to 5 | No (infiltrating)ix; Yes (non-infiltrating) | 4m-Underground Utilities Drinking Water Wellhead Protection Areas |

No (infiltrating); Yes (non-infiltrating) | 2 year - WHPA-B (infiltrating); None (non-infiltrating) |

| Enhanced swales (featuring check dams) | 1 | 5:1 to 10:1 | Decompaction if < 15 mm/hr | 1 to 3 | 5 to 15 | 0.5 to 6 | Noix | 4m- Building Foundation Underground Utilities |

No | 2 year - WHPA-B |

| Bioswales (Dry swales) | 1 (infiltrating); Not applicable (non-infiltrating) | 5:1 to 15:1 | Decompaction and underdrain recommended if < 15 mm/hr (infiltrating) |

1 to 3 | 5 to 10 | 0.5 to 6 | No (infiltrating)ix; Yes (non-infiltrating) | 4m (3m if impermeable liner is used) Building foundation, Underground utilities, Drinking Water Wellhead Protection Areas |

No (infiltrating); Yes (non-infiltrating) | 2 year - WHPA-B (infiltrating); None (non-infiltrating) |

| Exfiltration trenches | 1 | 5:1 to 10:1 | Not a constraint | 1 to 3 | 0 | < 15% | Noix | 4m- Building Foundation Underground Utilities, Trees, Drinking Water Wellhead Protection Areas |

No | 2 year - WHPA-B |

| Stormwater tree trenches | 1 | 5:1 to 15:1 | Underdrain recommended if < 15 mm/hr |

1 to 2 | 5 to 10 | 0 to 2 | No (infiltrating)ix; Yes (non-infiltrating) | 4m- Building Foundation Underground Utilities, Drinking Water Wellhead Protection Areas |

No (infiltrating); Yes (non-infiltrating) | 2 year - WHPA-B |

| Notes |

|---|

| i Minimum depth between the base of the facility and the elevation of the seasonally high water table or top of bedrock |

| ii Infiltration rate estimates based on measurements of hydraulic conductivity under field saturated conditions at the proposed location and depth of the practice |

| iii Vertical distance between the inlet and outlet of the LID practice |

| iv Percent of open pervious land on the site that is required for the LID practice |

| v Slope at the LID practice location |

| vi Suitable in pollution hot spots or runoff source areas where land uses or activities have the potential to generate highly contaminated runoff |

| vii Suitability in areas of karst geologic formations |

| viii Drinking Water Source Protection wellhead protection area time of travel |

| ix May be allowed under special circumstances and if appropriate mitigation actions are taken - please contact your local Source Protection Region (SPR) or Source Protection Area (SPA) for further information. You can find your associated SPR/SPA based on your location here and then visit their site here |

Source Water Protection in other Canadian jurisdictions[edit]

First Nations On-Reserve Source Water Protection Plan[edit]

Many, if not most First Nations' reserves lie outside of Ontario's designated SWR/SWAs. As a result of this in 2011 the Federal government issued a national assessment of on-reserve drinking water systems, they found that most First Nations did not have an existing SPP in place. After this assessment was completed, the First Nations On-Reserve Source Water Protection Plan was developed by Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development in partnership with the Alberta First Nations' Technical Services Advisory Group (TSAG), Siksika First Nation, Alberta and Dr. Robert Patrick from the Department of Geography and Planning of University of Saskatchewan.

The document is both a descriptive guide and real-world template to be used to help develop a SPP on reserve lands. It provides all necessary tools in developing a community based SPP by taking a watershed-scale approach to protecting freshwater supplies. The plan development is led by both Chief and Council of the community as the principal decision makers along with others responsible for landuse decisions and community planning initiatives (AAND, 2014[18])

First Nations Communities (Southwestern Ontario)[edit]

In an Ontario context, the the Chippewas of the Thames First Nation, the Oneida Nation of the Thames, the Munsee-Delaware Nation (CMO) and the Canadian Environmental Law Association (CELA) developed a partnership to create a series of Legal Toolkits for Source Water Protection in Indigenous Communities located along the Thames River in Southwestern Ontario. This partnership began in 2017 and they released a series of five (5) toolkits that discuss a host of issues with SPPs includes by-laws, agricultural leases, consultations, environmental rights and appeals, etc. they can be found below (CELA, 2019[19]):

- Legal Toolkit Report

- Legal Tool 1: By-laws as an Authority for Environmental Protection and Enforcement

- Legal Tool 2: Consultation and Accommodation Protocol to Advance Source Water Protection

- Legal Tool 3: Public Environmental Rights and Appeals Related to Source Waters

- Legal Tool 4: Considering Source Water within Agricultural Leases on First Nation Reserve Lands

- Legal Tool 5: Protecting Source Waters Under the Clean Water Act

In the South Georgian Bay Lake Source Protection Region there are three indigenous communities: Beausoleil First Nation, Chippewas of Georgina Island First Nation, and Chippewas of Rama First Nation. At this time, the Chippewas of Rama First Nation has opted into the source water protection process by passing a Band Council resolution in 2011 and announced the inclusion of their drinking water system within the Source Water Protection planning process back in 2014.

Nova Scotia[edit]

The Province of Nova Scotia (through Nova Scotia Environment - NSE) released their, Drinking Water Strategy for Nova Scotia, which provides a framework for managing both drinking water supplies, intakes and vulnerable areas across the province. The NSE published five (5) technical documents which provide guidance to practitioners on how to create and deliver source water protection plans, the overall processes it entails and solutions to problems that may occur.

Similar to Ontario the NSE requires either the local water utility company or the municipality itself to create an advisory committee made up of councillors, municipal engineers, landowners residents and businesses along with consultants to carry out technical requirements and steps. The committee must then map out the Water Protection Boundary with optional public consultation and input, after which known and potential contaminants and risks will be assessed dependent upon the activities that may pose a risk to source water supply areas. Then the advisory committee is tasked with developing and implementing a Source Water Protection Management Plan that includes the ABC's of source water protection:

- (A)quisition of land in source water supply areas to improve protection of water quality

- (B)y-laws to develop new municipal planning strategies and create new regulations and permits for work conducted in source water supply areas.

- (B)MPs and guidelines to best manage and monitor activities that take place in the water supply area

- (C)ontingency Plans for when an unexpected event occurs that threatens the source water area and the health of the local population

- (D)esignation, the Environment Act in Nova Scotia allows for areas to be created known as Designated Protected Water Areas. this allows a water utility or municipality to properly regulate activities that occur in these protected regions

- (E)ducation, the committee will work with stakeholders and users in the source water supply area to highlight important piece of information they should know when working in these areas regarding their role in protecting local drinking water and overall water stewardship BMPs.

Finally, the last step is to create a "Monitoring and Evaluation Plan", which sets up specific prescribed procedures for ongoing monitoring of the area to ensure water quality contaminants are mitigated and a formalized source water protection plan review process is implemented (Government of Nova Scotia, n.d.[21]). All of this information and more can be found here on Nova Scotia's Environment and Climate Change's Source Water Protection Home Page

British Columbia[edit]

In the province of British Columbia (BC) there are two (2) primary source water protection documents:

1. Drinking Water Protection Act (DWPA) - Covers both water source and system assessments within the province along with response plans to unmitigated risks 2. Drinking Water Protection Plans (DWPP) - Ordered and made required by the Minister of Health under the DWPA, 2001 [SBC 2001] Chapter 9 (Government of British Columbia, n.d.(a))[22]

The government of BC has created an excellent portal for water system operators and suppliers to access current resources and tools that help them understand their role and responsibilities under the DWPA, 2001 and includes the following:

- Drinking Water Source-to-Tap Guideline Document - provides a step by step approach to evaluating risks to drinking water that coincides with requirements within the DWPA, 2001

- Drinking Water Source-to-Tap Screening Tool - An alternative method for assessing risk in drinking water systems, the tool contains 97 questions and is a "question-and-answer" based document that allows drinking water officers to determine if a water supplier submitting the document needed to undertake a comprehensive assessment to further analyze associated risk and vulnerabilities

- Emergency Response Plan - Developed to help water officers develop their own emergency response plan in more rural areas that possess small water systems

- Guidance Document for Determining Ground Water at Risk of Containing Pathogens (GARP) - Developed for drinking water officers to determine if groundwater sources are at risk of certain pathogens.

- Water System Assessment User's Guide - Aids both operators and owners to assess their water system's safety and overall security.

- and more (Government of British Columbia, n.d.(B))[23]

BMP Selection & Pretreatment for SWP[edit]

With respect to potential contaminants or pollutants in stormwater surface runoff the types and levels of these contaminants varies widely depending on the associated activities, characteristics and makeup of the local source water area.

An area, for example that contains a high density of roads and industrial areas that require large amounts of de-icing road salt in the winter and experiences heavy traffic daily, make it a significant source of sodium, chloride, petroleum based hydrocarbons and heavy metals. On the other hand a source area such as a roof is only subject to atmospheric deposition of contaminants and isn't typically subjected to vehicular traffic, sand, salt nor other de-icing agents. As a result, roof runoff typically contains significantly lower levels of heavy metals, petroleum hydrocarbons and salt.

Certain source areas known as "pollution hot spots" have a higher chance to create contaminated surface level runoff due to given activities occurring and associated contaminant types present on site (e.g., vehicle fueling stations, landfills, certain agricultural practices, manufacturing and construction sites). It is important that stormwater management plans be developed with consideration of the different types of runoff source areas that will be present, and recognition of source areas with low to moderate contamination potential that represent opportunities for rainwater harvesting, permeable pavements and other stormwater infiltration practices. Furthermore, it is important to ensure that relatively clean runoff is not mixed with lesser quality runoff from surfaces that are subject to higher levels of contamination, rendering it less suitable for infiltration or harvesting.

A summary of stormwater source area types, associated runoff characteristics and stormwater BMP opportunities and pretreatment requirements is provided in the table below:

Stormwater Source Area |

Runoff Characteristics |

Opportunities |

Principles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foundation drains, slab underdrains, road or parking lot underdrains |

Relatively cool, clean water |

Suitable for infiltration or direct discharge to receiving watercourses in the area |

Should not be directed to stormwater management facility that receives road or parking lot runoff, so as not to mix relatively clean and contaminated runoff waters |

| Roof drains, roof terrace area drains, overflow from green roofs |

Moderately clean water, contaminants may include asphalt granules, low levels of hydrocarbons and metals from decomposition of roofing materials, animal droppings, natural organic matter and fall out from airborne pollutants, potentially warm water. |

|

Runoff should be treated with a sedimentation and/or filtration practice prior to infiltration. Where possible, runoff should not be directed to end-of-pipe facilities to capitalize on potential for infiltration or harvesting. Flow moderation (quantity control) prior to discharge to receiving watercourse is required. |

| Low and medium traffic roads and parking lots, driveways, pedestrian plazas, walkways |

Moderately clean water, contaminants may include low levels of sediment, de-icing salt constituents, hydrocarbons, metals and natural organic matter. Typically warm water. |

|

Runoff should be treated with a sedimentation and/or filtration practice prior to infiltration. Flow moderation (quantity control) prior to discharge to receiving watercourse is required. Harvested stormwater quality should be tested prior to use for non-potable purposes. |

| High traffic roads and parking lots |

Potential for high levels of contamination with sediment, deicing salt constituents hydrocarbons and metals. Typically warm water. |

|

Runoff should be treated with a sedimentation and/or filtration pretreatment practice prior to infiltration. |

| "Pollution hot spots" such as vehicle fueling, servicing or demolition areas, outdoor storage and handling areas for hazardous materials, some heavy industry/construction sites |

Potential for high levels of contamination with sediment, deicing salt constituents, hydrocarbons, metals, and other toxins. |

|

Runoff from these sources should not be infiltrated or used for irrigation. Spill containment or mitigation devices recommended contingent on size of storage facilities. |

External Resources[edit]

Below, find a list of valuable tools aimed at the general public, landowners, real estate agents, farmers and technical practitioners (consultants, operators, technicians, risk management officials, inspectors etc.) for Source Water Protection in the Province of Ontario:

- Landowners - What landowners can do to protect water quality & quantity

- Real Estate Agents - Drinking Water Source Protection in Ontario: What Every Real Estate Agent Should Know

- Farmers/Agriculturalists - AGRI-ACTION: Protecting water from field to faucet

- Risk Management Officials and Inspectors - Regulation of Drinking Water Threats under Clean Water Act Part IV

- Technical Practitioners - CTC Source Protection Region Education and Outreach resources including IPZs, WHPAs, Water Quality Threats, Road Salt, Snow Storage, Pesticides, Organic Solvents and DNAPLs.

- All Users - Source Water Protection Information Portal - An all in one hub developed by the Ministry of the Environment Conservation and Parks (MECP) to help users understand drinking water threats, updated SWP policies, access to the Source Protection Information Atlas (SPIA) Tool, and Technical Rules under the Clean Water Act.

References[edit]

- ↑ Conservation Ontario. 2022. Best Practices for Source Water Protection. Accessed 27 May 2022: https://conservationontario.ca/conservation-authorities/source-water-protection/

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Government of Ontario. 2021. Source protection. Environment and Energy - Drinking Water. 13 October 2021. Accessed: 26 May 2022. https://www.ontario.ca/page/source-protection#section-0

- ↑ Conservation Ontario. 2016. Protecting Our Sources of Drinking Water: Implementation of Source Protection Plans across Ontario. Written by: Chitra Gowda, 11 Oct. 2016. Accessed 27 May 2022: https://ijc.org/en/protecting-our-sources-drinking-water-implementation-source-protection-plans-across-ontario

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Credit Valley-Toronto and Region-Central Lake Ontario (CTC) Source Protection Region (SPR). 2019. Protecting our Drinking Water Sources. Accessed 26 May 2022. https://ctcswp.ca/app/uploads/2019/06/DOC_20190328_Magazine_DigitalSpreads_FNL.pdf

- ↑ Conservation Ontario. 2018. SWP Education & Outreach - Road Signage (English). Accessed 31 May 2022. https://conservationontario.ca/resources?tx_fefiles_files%5Baction%5D=show&tx_fefiles_files%5Bcontroller%5D=File&tx_fefiles_files%5Bfile%5D=389&cHash=88b06a201529f054e0a87582376f6c2a

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Halton-Hamilton Source Protection Region. 2010. Wellhead Protection Areas (WHPAs). Planning Process - Vulnerable Areas. Accessed 02 June 2022. http://protectingwater.ca/en/planning1e38.html?smocid=1440&parentcatid=841

- ↑ Government of Ontario. 2022. A guide for operators and owners of drinking water systems that serve designated facilities. 19 May 2022. Accessed 3 June 2022. https://www.ontario.ca/page/providing-safe-drinking-water-public-guide-owners-and-operators-non-residential-and-seasonal

- ↑ Vulnerability Assessment and Scoring of Wellhead Protection Areas - City of Hamilton, Ontario. Published April 2010. Prepared for the City of Hamilton - Public Works Department, Environment and Sustainable Infrastructure Division. http://protectingwater.ca/uploads/Documents/swp03%20-%20Appendix%20B%20-%20Hamilton%20Vulnerability%20Report%20v32-final.pdf

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Halton-Hamilton Source Protection Region. 2010. Intake Protection Zones (Lake Ontario). Accessed 2 June 2022. http://protectingwater.ca/planning.cfm?smocid=1437&parentcatid=841

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Cataraqui Source Protection Area. 2022. What is an Intake Protection Zone? Accessed 2 June 2022. https://cleanwatercataraqui.ca/resources/living-in-the-cspa/what-is-an-intake-protection-zone/

- ↑ EarthFx Incorporated. 2010. WHPA Vulnerability Analysis for the Region of Peel Wellfields, Ontario. Client: Region of Peel Infrastructure Planning. Consultant: Engineering and Construction Group. https://www.earthfx.com/?page_id=2205

- ↑ Government of Ontario. 2021. Clean Water Act, 2006: ONTARIO REGULATION 287/07: S.O. 2006, c. 22. Last amendment: 356/21 (1 June 2021). Accessed 3 June 2022. https://www.ontario.ca/laws/regulation/070287#BK3

- ↑ Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks. 2022. Source Protection Information Atlas. Powered by Land Information Ontario. Information is current as of: May 12, 2022. Accessed June 2 2022. https://www.lioapplications.lrc.gov.on.ca/SourceWaterProtection/index.html?viewer=SourceWaterProtection.SWPViewer&locale=en-CA

- ↑ TRCA. 2018. How Does This Affect Me? CTC Source protection Region. Accessed: 6 June 2022. https://ctcswp.ca/protecting-our-water/what-does-this-mean-for-me/

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Ministry of Environment Conservation and Parks (MECP). 2022. Best practices for source water protection - Drinking Water. Last Updated: 3 May, 2022. Accessed June 3 2022. https://www.ontario.ca/document/best-practices-source-water-protection#section-2

- ↑ CTC Source Protection Region. 2021. CTC Source Protection Region 2021 Annual Progress Report. Accessed 6 June 2022. https://ctcswp.ca/app/uploads/2022/05/RPT_20220501_CTCSPR_2021AnnualProgressReport_fnl.pdf)

- ↑ The Canadian Environmental Law Association (CELA), Chippewas of the Thames, Munsee-Delaware and Oneida Nation of the Thames (CMO). 2019. Legal and Policy Tools for Source Water Protection in Indigenous Communities - A Tri-First Nation (Chippewas of the Thames First Nation, Munsee-Delaware First Nation, Oneida Nation of the Thames) and Canadian Environmental Law Association Initiative. ISBN: 978-1-77189-939-0. Publication No. 1233. Published: 7 January 2019. Accessed 3 June 2022. https://cela.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/LEGAL-TOOLKIT-Source-Water-Protection-in-Indigenous-Communities_0.pdf

- ↑ Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development (AAND). 2014. First Nations On-Reserve Source Water Protection Plan Guide and Template. ISBN: 978-1-100-23120-4. https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/DAM/DAM-ISC-SAC/DAM-WTR/STAGING/texte-text/source_1398366907537_eng.pdf

- ↑ Canadian Environmental Law Association. 2019. Source Water Protection in Indigenous Communities Legal Tool Kits. Accessed 7 June 2022. https://cela.ca/source-water-protection-in-indigenous-communities/

- ↑ Ministry of Health Services and Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection. 2004. Drinking Water Source-to-Tap Screening Tool. Accessed 6 June 2022. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/air-land-water/water/documents/bc_drinking_water_screening_tool.pdf

- ↑ Government of Nova Scotia. n.d. Developing a Municipal Source Water Protection Plan. A Guide for Water Utilities and Municipalities. Accessed June 7 2022. https://novascotia.ca/nse/water/docs/WaterProtectionPlanSummary.pdf

- ↑ Government of British Columbia. n.d. Drinking Water Protection Planning. Current Health Topics. Accessed June 7 2022. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/about-bc-s-health-care-system/office-of-the-provincial-health-officer/current-health-topics/drinking-water-protection-planning#:~:text=In%20BC%2C%20there%20are%20two,of%20Health%20under%20the%20Act.

- ↑ Government of British Columbia. n.d. Resources for Water System Operators. Drinking Water Quality. Accessed June 7 2022. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/environment/air-land-water/water/water-quality/drinking-water-quality/resources-for-water-system-operators#source-to-tap-screening

- ↑ Müller, A., Österlund, H., Marsalek, J. and Viklander, M. 2020. The pollution conveyed by urban runoff: A review of sources. Science of the Total Environment, 709, p.136125. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969719361212#f0010