Difference between revisions of "Sedimentation"

(→table) |

ChristineLN (talk | contribs) |

||

| (34 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | [[File:Screenshot 2025-07-09 145748.png|500px|thumb|right|Sedimentation is the process where particles suspended in a fluid settle to the bottom due to gravity.]] | |

| − | Sedimentation is a fundamental process used in stormwater treatment to remove | + | == Overview == |

| + | |||

| + | <imagemap> | ||

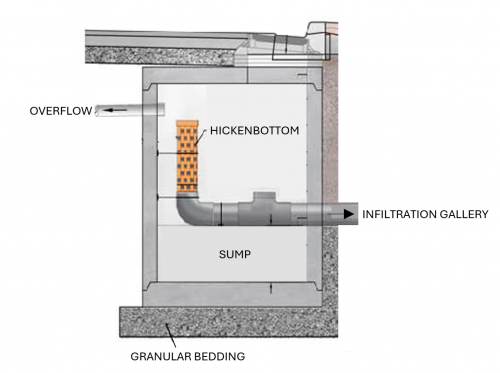

| + | File:Screenshot 2025-07-11 113242.png|thumb|500px|This cross-section of a road from the Markham Municipal Green Road Pilot Project shows a primary inlet connected to a catchbasin sump with a hickenbottom-style riser, promoting sedimentation before water reaches the infiltration gallery. Sediment should be removed from the catchbasin regularly. Image adapted from Schollen & Company Inc (STEP, 2018). <ref>Sustainable Technologies Evaluation Program. 2018. The Markham Municipal Green Road Pilot Project. https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2018/12/Markham-Green-Road-Case-Study_FINAL.pdf</ref> <span style="color:red">''Explore this image map with your cursor and click on highlighted labels to learn more on the Wiki.''</span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | rect 48 212 323 296 [[Overflow]] | ||

| + | rect 778 436 1143 544 [[Infiltration trenches|Infiltration]] | ||

| + | rect 367 523 699 641 [[Inlet sumps: Gallery|Inlet sump]] | ||

| + | rect 388 261 557 439 [[Pretreatment]] | ||

| + | rect 493 7 820 166 [[Inlets|Inlet]] | ||

| + | rect 208 704 775 845 [[Aggregates|Granular bedding]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | </imagemap> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sedimentation is a fundamental process used in stormwater treatment to remove suspended solids from runoff. It relies on gravity to deposit suspended sediment and debris into a designated settling area for later removal. Many pollutants that adhere to solids, such as metals, phosphorus, and hydrocarbons, are also removed through this process. | ||

Stormwater treatment practices that primarily use sedimentation include: | Stormwater treatment practices that primarily use sedimentation include: | ||

* Stormwater [[wet ponds]] and [[dry ponds]] | * Stormwater [[wet ponds]] and [[dry ponds]] | ||

| − | * Underground storage tanks and chambers | + | * Underground storage tanks and [[Rainwater harvesting#Cisterns|chambers]] |

* [[Stormwater wetlands]] | * [[Stormwater wetlands]] | ||

| − | * [[Oil grit separators (OGS)]] | + | * [[Oil and grit separators (OGS)]] |

| − | * | + | * Catch basins and [[pre-treatment]] sumps |

* [[Vegetated swales]] | * [[Vegetated swales]] | ||

| − | + | == Types of settling == | |

| − | Sedimentation occurs in two main forms: | + | Sedimentation occurs in two main forms (Minton, 2013)<ref>Minton, G. 2013. The Principles of Gravity Separation. https://www.stormwater.com/stormwater-bmps/article/13008476/the-principles-of-gravity-separation</ref>: |

'''Dynamic Settling''' – Takes place during active storm flow conditions when runoff is moving through the system. | '''Dynamic Settling''' – Takes place during active storm flow conditions when runoff is moving through the system. | ||

| Line 18: | Line 32: | ||

Practices such as ponds and wetlands rely on quiescent settling, whereas systems like oil grit separators and catch basins rely more on dynamic settling. The effectiveness of sedimentation systems is largely governed by the surface loading rate (SLR), which is the rate at which water is introduced to the settling area. Higher SLRs generally result in lower pollutant removal efficiency. | Practices such as ponds and wetlands rely on quiescent settling, whereas systems like oil grit separators and catch basins rely more on dynamic settling. The effectiveness of sedimentation systems is largely governed by the surface loading rate (SLR), which is the rate at which water is introduced to the settling area. Higher SLRs generally result in lower pollutant removal efficiency. | ||

| − | + | == Key design parameters == | |

The performance of sedimentation systems depends on several factors: | The performance of sedimentation systems depends on several factors: | ||

| Line 29: | Line 43: | ||

'''Particle Size Distribution''' – Determines the settling velocity of solids in runoff. | '''Particle Size Distribution''' – Determines the settling velocity of solids in runoff. | ||

| − | '''Inlet and Outlet Design''' – Properly designed structures reduce resuspension and short-circuiting of flow. | + | '''[[Inlet]] and Outlet Design''' – Properly designed structures reduce resuspension and short-circuiting of flow. |

| − | + | <br> | |

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |+Permanent pool storage, surface loading rates and detention times for sedimentation practices. Calculations are based on a one hectare drainage area with 85% imperviousness, peak flow rate for 4 hour Chicago distribution for 25 mm event and runoff coefficient of 0.81.<ref>References include: MOE, 2003; City of Toronto catch basin standard (T 705.010); OGS vendor technical manuals, TRCA OGS sizing review tool.</ref> | ||

|- | |- | ||

! Practice | ! Practice | ||

| Line 60: | Line 75: | ||

| colspan="6" | '''Pre-treatment Practices (approx. 30-50% TSS removal)''' | | colspan="6" | '''Pre-treatment Practices (approx. 30-50% TSS removal)''' | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Oil Grit | + | | Oil Grit Separator |

| 12 | | 12 | ||

| 4.7 | | 4.7 | ||

| Line 75: | Line 90: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | == Particle settling and particle size distribution == | |

Settling velocity is influenced by particle size, shape, specific gravity, and water temperature. Coarser particles settle faster, whereas fine silts and organic matter take longer. Temperature affects viscosity, meaning lower temperatures reduce settling efficiency. Understanding particle size distributions at a site is critical for designing effective sedimentation systems. | Settling velocity is influenced by particle size, shape, specific gravity, and water temperature. Coarser particles settle faster, whereas fine silts and organic matter take longer. Temperature affects viscosity, meaning lower temperatures reduce settling efficiency. Understanding particle size distributions at a site is critical for designing effective sedimentation systems. | ||

| − | Research has shown wide variations in particle sizes in urban runoff, influenced by factors such as native soil texture, tree canopy cover, traffic levels, and road maintenance practices. While laboratory analyses help determine particle size, field studies provide more practical insights into sedimentation system performance. | + | Research has shown wide variations in particle sizes in urban runoff, influenced by factors such as native soil texture, tree canopy cover, traffic levels, and road maintenance practices. While laboratory analyses help determine particle size, field studies provide more practical insights into sedimentation system performance. The studies cited in the table below show a range of values found in literature. D10 is the diameter at which 10% of the particle size distribution falls below, D50 is the diameter at |

| − | + | which 50% of the particle size distribution falls below, and D90 is the diameter at which 90% of the particle size distribution falls below. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |+Comparison of particle size distributions from previous studies in cold climates (STEP, 2012)<ref name = "STEP2012">Sustainable Technologies Evaluation Program. 2012. Characterization of Particle Size Distributions of | ||

| + | Runoff from High Impervious Urban Catchments in the Greater Toronto Area. https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2013/03/PSD-2012-final.pdf</ref> | ||

|- | |- | ||

! Land use | ! Land use | ||

! Number of <br />observations | ! Number of <br />observations | ||

! Location | ! Location | ||

| − | ! | + | ! Sampling<br />location |

| − | ! | + | ! Sampling<br />method |

! Analytical<br />method | ! Analytical<br />method | ||

| − | ! | + | ! D<sub>10</sub><br />/µm |

| − | ! | + | ! D<sub>50</sub><br />/µm |

| − | ! | + | ! D<sub>90</sub><br />/µm |

! Source | ! Source | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 116: | Line 121: | ||

| 5.9 | | 5.9 | ||

| 44 | | 44 | ||

| − | | SWAMP<ref> | + | | (SWAMP, 2005)<ref name="SWAMP">SWAMP. 2005. Synthesis of Monitoring Studies Conducted Under the Stormwater Assessment Monitoring and Performance Program. https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2013/01/Final_SWAMP_Synthesis.pdf</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| Parking<br />lot | | Parking<br />lot | ||

| Line 127: | Line 132: | ||

| 9.0 | | 9.0 | ||

| 92 | | 92 | ||

| − | | SWAMP | + | | (SWAMP, 2005)<ref name="SWAMP"/> |

|- | |- | ||

| Commercial<br />parking lot | | Commercial<br />parking lot | ||

| Line 138: | Line 143: | ||

| 8.5 | | 8.5 | ||

| 25.9 | | 25.9 | ||

| − | | | + | | Lab report, 2010 |

|- | |- | ||

| Public bus<br />yard | | Public bus<br />yard | ||

| Line 149: | Line 154: | ||

| 19.2 | | 19.2 | ||

| 154.1 | | 154.1 | ||

| − | | | + | | (Stantec, 2008) |

|- | |- | ||

| Commerical<br />parking lot | | Commerical<br />parking lot | ||

| Line 160: | Line 165: | ||

| 55 | | 55 | ||

| 500<br /> | | 500<br /> | ||

| − | | | + | | (Horwatich & Bannerman, 2010)<ref>Horwatich, J.A. and Bannerman, R.T., 2010, Parking lot runoff quality and treatment efficiency of a |

| + | stormwater-filtration device, Madison, Wisconsin, 2005–07: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific | ||

| + | Investigations Report 2009–5196, 50 p</ref> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Mixed use | | Mixed use | ||

| Line 171: | Line 178: | ||

| 42 | | 42 | ||

| 200 | | 200 | ||

| − | | | + | | (Selbig & Bannerman, 2011)<ref name="Selbig">Selbig , W. R., & Bannerman, R. T., 2011. Characterizing the Size Distribution of Particles in Urban |

| + | Stormwater by Use of Fixed-Point Sample-Collection Methods. Open-File Report 2011–1052, | ||

| + | U.S. Department of the Interior and U.S. Geological Survey, Reston.</ref> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Parking lot | | Parking lot | ||

| Line 182: | Line 191: | ||

| 54 | | 54 | ||

| 350 | | 350 | ||

| − | | | + | | (Selbig & Bannerman, 2011)<ref name="Selbig"/> |

|- | |- | ||

| Parking lot | | Parking lot | ||

| Line 193: | Line 202: | ||

| 46 | | 46 | ||

| - | | - | ||

| − | | | + | | (Fowler et al, 2009)<ref>Fowler, G.D.; Roseen, R.M.; Ballestero, T.P.; Guo, Qizhong; and Houle, James, 2009, Sediment |

| + | monitoring bias by autosampler in comparison with whole volume sampling for parking lot runoff, | ||

| + | in Proceedings of the World Environmental and Water Resources Congress 2009—Great Rivers, | ||

| + | Kansas City, Mo., May 17–21, 2009: p. 1514-1522</ref> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Mixed use<br />(roads) | | Mixed use<br />(roads) | ||

| Line 204: | Line 216: | ||

| 52.5 | | 52.5 | ||

| 145 | | 145 | ||

| − | | | + | | (Winston & Witter, 2019)<ref>Winston, R. J., & Witter, J. D. 2019. Evaluating the particle size distribution and gross solids contribution of stormwater runoff from Ohio’s roads (Final Report, State Job Number 135258). Ohio Department of Transportation, Office of Statewide Planning & Research.</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| Mixed use | | Mixed use | ||

| Line 215: | Line 227: | ||

| 16.4 | | 16.4 | ||

| 55.1 | | 55.1 | ||

| − | | | + | | (STEP, 2012)<ref name = "STEP2012"/> |

|- | |- | ||

| Parking lot | | Parking lot | ||

| Line 226: | Line 238: | ||

| 12.4 | | 12.4 | ||

| 55.2 | | 55.2 | ||

| − | | | + | | (STEP, 2012)<ref name = "STEP2012"/> |

|} | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Best practices for sedimentation-based stormwater treatment == | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Design for Adequate Surface Area''' – Systems should have sufficient area to slow down flow and enhance settling. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Maintain Low Surface Loading Rates''' – Lower SLRs improve treatment performance. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Use Pre-Treatment Systems''' – Oil grit separators and catch basins can extend the life of downstream sedimentation systems. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Incorporate Periodic Maintenance''' – Regular sediment removal prevents resuspension and system clogging. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Account for Seasonal Variability''' – Adjust design parameters based on temperature effects on settling velocity. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

Latest revision as of 18:34, 18 July 2025

Overview[edit]

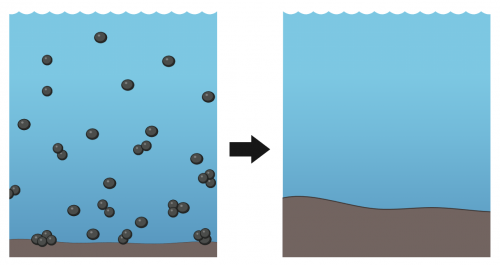

Sedimentation is a fundamental process used in stormwater treatment to remove suspended solids from runoff. It relies on gravity to deposit suspended sediment and debris into a designated settling area for later removal. Many pollutants that adhere to solids, such as metals, phosphorus, and hydrocarbons, are also removed through this process. Stormwater treatment practices that primarily use sedimentation include:

- Stormwater wet ponds and dry ponds

- Underground storage tanks and chambers

- Stormwater wetlands

- Oil and grit separators (OGS)

- Catch basins and pre-treatment sumps

- Vegetated swales

Types of settling[edit]

Sedimentation occurs in two main forms (Minton, 2013)[2]:

Dynamic Settling – Takes place during active storm flow conditions when runoff is moving through the system.

Quiescent Settling – Occurs between storm events when water is retained in a storage system, allowing suspended particles to settle under still conditions.

Practices such as ponds and wetlands rely on quiescent settling, whereas systems like oil grit separators and catch basins rely more on dynamic settling. The effectiveness of sedimentation systems is largely governed by the surface loading rate (SLR), which is the rate at which water is introduced to the settling area. Higher SLRs generally result in lower pollutant removal efficiency.

Key design parameters[edit]

The performance of sedimentation systems depends on several factors:

Permanent Pool Volume – The volume of water permanently stored in a system, aiding quiescent settling.

Surface Loading Rate – The volume of water per unit surface area per unit time.

Detention Time – The length of time water remains in the system before discharge.

Particle Size Distribution – Determines the settling velocity of solids in runoff.

Inlet and Outlet Design – Properly designed structures reduce resuspension and short-circuiting of flow.

| Practice | Permanent Pool /m3/Ha |

Surface Area /m2/Ha |

Surface Loading Rate /L/min/m2 |

Detention Time /hrs |

Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhanced Treatment Practices (80% TSS removal) | |||||

| Wet ponds/ Underground Tanks | 250 | 167 | 33 | >24 | Underground tanks sized like ponds, average permanent pool depth =1.5m |

| Stormwater Wetland | 140 | 622 | 8.8 | >24 | Average depth =0.225m |

| Pre-treatment Practices (approx. 30-50% TSS removal) | |||||

| Oil Grit Separator | 12 | 4.7 | 1177 | Negligible | Varies by manufacturer. 2.44m (8ft) diameter unit with permanent pool depth of 2.6m. 60% removal objective. |

| Catch Basin | 1.6 | 1.8 | 3054 | Negligible | 5 catch basins (0.6 x 0.6m) per Hectare. Permanent pool depth of 0.9m. |

Particle settling and particle size distribution[edit]

Settling velocity is influenced by particle size, shape, specific gravity, and water temperature. Coarser particles settle faster, whereas fine silts and organic matter take longer. Temperature affects viscosity, meaning lower temperatures reduce settling efficiency. Understanding particle size distributions at a site is critical for designing effective sedimentation systems.

Research has shown wide variations in particle sizes in urban runoff, influenced by factors such as native soil texture, tree canopy cover, traffic levels, and road maintenance practices. While laboratory analyses help determine particle size, field studies provide more practical insights into sedimentation system performance. The studies cited in the table below show a range of values found in literature. D10 is the diameter at which 10% of the particle size distribution falls below, D50 is the diameter at which 50% of the particle size distribution falls below, and D90 is the diameter at which 90% of the particle size distribution falls below.

| Land use | Number of observations |

Location | Sampling location |

Sampling method |

Analytical method |

D10 /µm |

D50 /µm |

D90 /µm |

Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed residential |

66 | GTA | Storm sewer |

Auto- sampler |

Coulter counter particle analyzer |

0.9 | 5.9 | 44 | (SWAMP, 2005)[5] |

| Parking lot |

44 | Markham | Storm sewer |

Auto- sampler |

Coulter counter particle analyzer |

2.0 | 9.0 | 92 | (SWAMP, 2005)[5] |

| Commercial parking lot |

1 | Calgary | Storm sewer |

NA | Coulter counter particle analyzer |

2.1 | 8.5 | 25.9 | Lab report, 2010 |

| Public bus yard |

11 | Toronto | Storm sewer |

Auto- sampler |

Micro-imaging | 4.0 | 19.2 | 154.1 | (Stantec, 2008) |

| Commerical parking lot |

45 | Madison, WI |

Storm sewer |

Auto- sampler |

Wet sieve (>32um); particle analyzer (<32um) |

<2 | 55 | 500 |

(Horwatich & Bannerman, 2010)[6] |

| Mixed use | 20 | Madison, WI |

Storm sewer |

Auto- sampler |

Wet sieve (>32um); particle analyzer (<32um) |

<2 | 42 | 200 | (Selbig & Bannerman, 2011)[7] |

| Parking lot | 94 | Madison, WI |

Storm sewer |

Auto- sampler |

Wet sieve (>32 um); particle analyzer (<32um) |

2 | 54 | 350 | (Selbig & Bannerman, 2011)[7] |

| Parking lot | 18 | New Hampshire |

Storm sewer |

Auto- sampler |

Particle analyzer | - | 46 | - | (Fowler et al, 2009)[8] |

| Mixed use (roads) |

176 | Ohio | Catch basin |

Auto- sampler |

Coulter counter particle analyzer |

11 | 52.5 | 145 | (Winston & Witter, 2019)[9] |

| Mixed use | 7 | Toronto |

Storm outfall |

Grab | Coulter counter particle analyzer |

4.0 | 16.4 | 55.1 | (STEP, 2012)[4] |

| Parking lot | 12 | Toronto, Vaughan, Brampton |

Direct runoff, man hole |

Grab | Coulter counter particle analyzer |

2.6 | 12.4 | 55.2 | (STEP, 2012)[4] |

Best practices for sedimentation-based stormwater treatment[edit]

Design for Adequate Surface Area – Systems should have sufficient area to slow down flow and enhance settling.

Maintain Low Surface Loading Rates – Lower SLRs improve treatment performance.

Use Pre-Treatment Systems – Oil grit separators and catch basins can extend the life of downstream sedimentation systems.

Incorporate Periodic Maintenance – Regular sediment removal prevents resuspension and system clogging.

Account for Seasonal Variability – Adjust design parameters based on temperature effects on settling velocity.

References[edit]

- ↑ Sustainable Technologies Evaluation Program. 2018. The Markham Municipal Green Road Pilot Project. https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2018/12/Markham-Green-Road-Case-Study_FINAL.pdf

- ↑ Minton, G. 2013. The Principles of Gravity Separation. https://www.stormwater.com/stormwater-bmps/article/13008476/the-principles-of-gravity-separation

- ↑ References include: MOE, 2003; City of Toronto catch basin standard (T 705.010); OGS vendor technical manuals, TRCA OGS sizing review tool.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Sustainable Technologies Evaluation Program. 2012. Characterization of Particle Size Distributions of Runoff from High Impervious Urban Catchments in the Greater Toronto Area. https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2013/03/PSD-2012-final.pdf

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 SWAMP. 2005. Synthesis of Monitoring Studies Conducted Under the Stormwater Assessment Monitoring and Performance Program. https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2013/01/Final_SWAMP_Synthesis.pdf

- ↑ Horwatich, J.A. and Bannerman, R.T., 2010, Parking lot runoff quality and treatment efficiency of a stormwater-filtration device, Madison, Wisconsin, 2005–07: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2009–5196, 50 p

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Selbig , W. R., & Bannerman, R. T., 2011. Characterizing the Size Distribution of Particles in Urban Stormwater by Use of Fixed-Point Sample-Collection Methods. Open-File Report 2011–1052, U.S. Department of the Interior and U.S. Geological Survey, Reston.

- ↑ Fowler, G.D.; Roseen, R.M.; Ballestero, T.P.; Guo, Qizhong; and Houle, James, 2009, Sediment monitoring bias by autosampler in comparison with whole volume sampling for parking lot runoff, in Proceedings of the World Environmental and Water Resources Congress 2009—Great Rivers, Kansas City, Mo., May 17–21, 2009: p. 1514-1522

- ↑ Winston, R. J., & Witter, J. D. 2019. Evaluating the particle size distribution and gross solids contribution of stormwater runoff from Ohio’s roads (Final Report, State Job Number 135258). Ohio Department of Transportation, Office of Statewide Planning & Research.