Difference between revisions of "Swales"

Tvanseters (talk | contribs) m (→Overview) |

|||

| (35 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[File:20161024 100338 550x550.jpg|thumb|Bioswale, County Court Boulevard, Brampton]] | + | [[File:20161024 100338 550x550.jpg|thumb|500px|Bioswale, County Court Boulevard, Brampton]] |

This article is about installations designed to capture and convey surface runoff along a vegetated channel, whilst also promoting infiltration. <br> | This article is about installations designed to capture and convey surface runoff along a vegetated channel, whilst also promoting infiltration. <br> | ||

| − | For underground conveyance which | + | For underground conveyance systems which promote infiltration, see [[Exfiltration trenches]]. |

{{TOClimit|2}} | {{TOClimit|2}} | ||

==Overview== | ==Overview== | ||

| − | Swales are linear landscape features consisting of a drainage channel with gently sloping sides. Underground they may be filled with engineered soil and/or contain a water storage layer of coarse gravel material. Two variations on a basic swale are recommended as low impact development strategies, although using a combination | + | Swales are linear landscape features consisting of a drainage channel with gently sloping sides. Underground they may be filled with engineered soil and/or contain a water storage layer of coarse gravel material. Two variations on a basic swale are recommended as low impact development strategies, although using a combination of both designs may increase the benefits:<br> |

| − | '''[[Bioswales]]''' are sometimes referred to as 'dry swales', 'vegetated swales', or 'water quality swales'. This type of BMP is form of [[bioretention]] with a long linear shape (surface area typically >2:1 length:width) and a slope which | + | '''[[Bioswales]]''' are sometimes referred to as 'dry swales', 'vegetated swales', or 'water quality swales'. This type of BMP is form of [[bioretention]] with a long, linear shape (surface area typically >2:1 length:width) and a slope which conveys water and generally contains various water tolerant [[vegetation]],<br> |

'''[[Enhanced grass swales]]''' are a lower maintenance alternative, but generally have lower stormwater management potential. The enhancement over a basic grass swale is in the addition of [[check dams]] to slow surface water flow and create small temporary pools of water which can infiltrate the underlying soil.<br> | '''[[Enhanced grass swales]]''' are a lower maintenance alternative, but generally have lower stormwater management potential. The enhancement over a basic grass swale is in the addition of [[check dams]] to slow surface water flow and create small temporary pools of water which can infiltrate the underlying soil.<br> | ||

'''Grass swales''' are a relatively common landscape feature already and a great opportunity for retrofit, to reduce flow and improve water quality by encouraging settling and infiltration behind a series of check dams. <br> | '''Grass swales''' are a relatively common landscape feature already and a great opportunity for retrofit, to reduce flow and improve water quality by encouraging settling and infiltration behind a series of check dams. <br> | ||

'''[[Retention swales]]''' can be imagined as linear, sloped [[dry ponds]]. They typically make relatively small contributions to water volume and quality control than many other BMPs, but they may feature as part of a site-wide treatment train approach. | '''[[Retention swales]]''' can be imagined as linear, sloped [[dry ponds]]. They typically make relatively small contributions to water volume and quality control than many other BMPs, but they may feature as part of a site-wide treatment train approach. | ||

| − | {{float right|{{#widget:YouTube|id= | + | |

| + | |||

| + | Take a look at the downloadable Enhanced Grass Swales Factsheet below for a .pdf overview of this LID Best Management Practice: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Clickable button|[[File:Enhanced swale.png|150 px|link=https://wiki.sustainabletechnologies.ca/images/8/85/Swales_final_Update.pdf]]}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{float right|{{#widget:YouTube|id=bau3CeMjvak}}}} | ||

{{textbox|Swales are an ideal technology for: | {{textbox|Swales are an ideal technology for: | ||

| − | *Sites with long linear landscaped areas, such as parking lots | + | *Sites with long, linear landscaped areas, such as parking lots |

*Connecting with one or more other types of LID}} | *Connecting with one or more other types of LID}} | ||

| Line 37: | Line 44: | ||

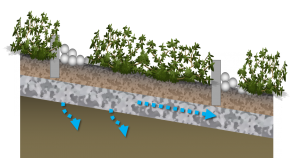

[[File:Bioswale.png||thumb|Bioswale with check dams<br> (vertical scale exaggerated)]] | [[File:Bioswale.png||thumb|Bioswale with check dams<br> (vertical scale exaggerated)]] | ||

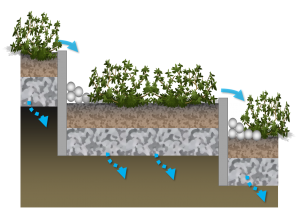

[[File:Stepped cells.png||thumb|Stepped bioretention cells alternative for slopes >6 % <br> (vertical scale exaggerated)]] | [[File:Stepped cells.png||thumb|Stepped bioretention cells alternative for slopes >6 % <br> (vertical scale exaggerated)]] | ||

| − | A linear design (surface area typically >2:1 length:width) is a common feature of | + | Enhanced swales and in some cases bioswales include check dams that can be designed to pond substantial volumes of water on the swale surface between flow events, so provide both stormwater conveyance and infiltration functions. |

| − | *An absolute minimum width | + | For information about constraints to infiltration practices, and approaches and tools for identifying and designing within them see [[Infiltration]]. For guidance on infiltration testing and selecting a design infiltration rate see [[Design infiltration rate]]. |

| − | *Grassed swales are usually mown as part of routine maintenance, so the cross section will be triangular or | + | |

| + | A linear design (surface area typically >2:1 length:width) is a common feature of swales: | ||

| + | *An absolute minimum width of 0.6 m is required for bioswales to promote healthy plant growth, and to facilitate construction, | ||

| + | *Grassed swales are usually mown as part of routine maintenance, so the cross section will be triangular or trapezoidal in shape with maximum side slopes of 1:3. The minimum width for this type would be 2 m. See [[Enhanced grass swales#Best cross sections| Best cross sections]] | ||

Swales may be graded along longitudinal slopes between 0.5 - 6 %: | Swales may be graded along longitudinal slopes between 0.5 - 6 %: | ||

*Between 1 - 6 %, check dams are recommended to bring the compensation gradient <1 %. | *Between 1 - 6 %, check dams are recommended to bring the compensation gradient <1 %. | ||

*Slopes > 6% can accommodate a series of stepped [[bioretention cells]], each overflowing into the next with a spillway. | *Slopes > 6% can accommodate a series of stepped [[bioretention cells]], each overflowing into the next with a spillway. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | For a table summarizing information on planning considerations and site constraints see [[Site considerations]]. | ||

==Design== | ==Design== | ||

| Line 49: | Line 62: | ||

<h3>Pretreatment and inlets</h3> | <h3>Pretreatment and inlets</h3> | ||

| − | To minimize erosion and maximize the functionality of the swale, sheet flow of surface water should be directed into the side of the BMP. [[Gravel diaphragms]], [[vegetated filter strips]] and shallow side slopes are ideal. Alternatively, a series of curb inlets can be employed, where each has some form of flow | + | To minimize erosion and maximize the functionality of the swale, sheet flow of surface water should be directed into the side of the BMP. [[Gravel diaphragms]], [[vegetated filter strips]] and shallow side slopes are ideal. Alternatively, a series of curb inlets can be employed, where each has some form of flow spreader incorporated. Single point inflow can cause increased erosion and sedimentation, which will damage vegetation and contribute to BMP failure. Again, flow spreading devices can mitigate these processes, where concentrated point inflow is required. |

| + | |||

| + | ==Inspection and Maintenance== | ||

| + | Maintenance requirements for [[enhanced swales|enhanced grass swales]], and swales is similar to vegetated filter strips and typically involve a low level of activity after [[vegetation]] becomes established. [[Grasses|Grass]] channel maintenance procedures are already in place at many municipal public works and transportation departments. These procedures should be compared to the recommendations provided on the [[Inspection and Maintenance: Enhanced Swales]] page to assure that the infiltration and water quality | ||

| + | benefits of enhanced grass swales are preserved. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Routine roadside ditch maintenance practices such as scraping and re-grading should be avoided at swale locations. Vehicles should not be parked or driven on grass swales. For routine mowing, the lightest possible mowing equipment should be used to prevent soil compaction. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For swales located on private property, the property owner, resident or manager is responsible for maintenance as outlined in a legally binding maintenance agreement. Roadside | ||

| + | swales in residential areas generally receive routine maintenance from homeowners who should be advised regarding recommended maintenance activities and ensure they do not build anything within or on the channel of the swale which could result in flooding or pooling on theirs or their neighbours' properties. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | Take a look at the [[Inspection and Maintenance: Enhanced Swales]] page by clicking below for further details about proper inspection and maintenance practices: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Clickable button|[[File:Cover Photo swales.PNG|150 px|link=https://wiki.sustainabletechnologies.ca/index.php title=Inspection_and_Maintenance:_Enhanced_Swales&action=edit]]}} | ||

==Performance== | ==Performance== | ||

| − | + | An evaluation of swales and roadside ditches was published by STEP in 1999. The project page and additional tools are available [https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/home/urban-runoff-green-infrastructure/low-impact-development/swales-and-roadside-ditches/ here]. | |

| − | ===Bioswales=== | + | ===[[Bioswales]]=== |

{{:Bioswales: Performance}} | {{:Bioswales: Performance}} | ||

| − | ===Enhanced grass swales=== | + | Click on the citations above to view the performance of these features based upon specifics (i.e. drainage area to size ratio to achieve the reduction mentioned) in the table. |

| + | |||

| + | ===[[Enhanced swales| Enhanced grass swales]]=== | ||

| + | See Performance section on Enhanced swale page link above for additional information. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Recent research indicates that a conservative runoff reduction rate of 10 to 20% can be used depending on whether soils fall in [[Soil groups| hydrologic soil groups A/B or C/D,]] respectively. The runoff reduction rates can be doubled if the native soils on which the swale is located have been tilled to a depth of 300 mm and amended with compost to achieve an organic content of between 8 and 15% by weight or 30 to 40% by volume. The main contributing factors that influence runoff reduction rates for swales are: | ||

| + | * Native [[Soil groups|soil]] types | ||

| + | * [[Grading|Slope]] | ||

| + | * [[Vegetation|Vegetative cover]] and, | ||

| + | * [[Enhanced swales: Specifications|Length of the swale.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | {|class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |+Volumetric runoff reduction from enhanced swales | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !'''LID Practice''' | ||

| + | !'''Location''' | ||

| + | !'''<u><span title="Note: Runoff reduction estimates are based on differences between runoff volume from the practice and total precipitation over the period of monitoring unless otherwise stated." >Runoff Reduction*</span></u>''' | ||

| + | !'''Reference''' | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |rowspan="8" style="text-align: center;" | Grass Swale | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |Brampton | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |15 to 35%, | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |[https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2020/11/CC-Bioswale-Tech-brief-2018-FINAL.pdf| STEP (2018)]<ref>Sustainable Technologies Evaluation Program. Effectiveness of Retrofitted Roadside Biofilter Swales - County Court Boulevard, Brampton. Technical Brief. https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2020/11/CC-Bioswale-Tech-brief-2018-FINAL.pdf. https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2020/11/CC-Bioswale-Tech-brief-2018-FINAL.pdf</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |Sweden | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |40 to 55%, | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |Rujner ''et al''. (2016)<ref>Rujner, H., Leonhardt, G., Perttu, A.M., Marsalek, J. and Viklander, M. 2016. Advancing green infrastructure design: Field evaluation of grassed urban drainage swales. Modélisation/Models-Contrôle à la source/Source control. http://documents.irevues.inist.fr/bitstream/handle/2042/60477/3B7P03-124RUJ.pdf</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |Seoul, Korea | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |40 to 75%, | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |Rujner ''et al''. (2016)<ref>Rujner, H., Leonhardt, G., Perttu, A.M., Marsalek, J. and Viklander, M. 2016. Advancing green infrastructure design: Field evaluation of grassed urban drainage swales. Modélisation/Models-Contrôle à la source/Source control. http://documents.irevues.inist.fr/bitstream/handle/2042/60477/3B7P03-124RUJ.pdf</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |Maryland | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |59% | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |Davis ''et al''. (2012)<ref>Davis, A.P., Stagge, J.H., Jamil, E. and Kim, H. 2012. Hydraulic performance of grass swales for managing highway runoff. Water research, 46(20), pp.6775-6786. http://www.jstagge.com/assets/papers/Hydraulic%20performance%20of%20grass%20swales%20for%20managing.pdf </ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |Los Angeles | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |52.5%, | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |Ackerman and Stein (2008)<ref>Ackerman, D. and Stein, E.D. 2008. Evaluating the effectiveness of best management practices using dynamic modeling. Journal of Environmental Engineering, 134(8), pp.628-639. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Eric-Stein-2/publication/228910558_Evaluating_the_Effectiveness_of_Best_Management_Practices_Using_Dynamic_Modeling/links/0912f509278915fc77000000/Evaluating-the-Effectiveness-of-Best-Management-Practices-Using-Dynamic-Modeling.pdf</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |Various Locations | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |40% | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |Strecker ''et al''.(2004)<ref>Strecker, E., Quigley, M., Urbonas, B., Jones, J. 2004. State-of-the-art in comprehensive approaches to stormwater. The Water Report. Issue 6. August 15,2004. </ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |France | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |27 to 41% | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |Barrett ''et al''. (2004)<ref>Barrett, M.E. 2008. Comparison of BMP Performance Using the International BMP Database. Journal of Irrigation and Drainage Engineering. September/October. pp. 556-561 </ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |Virginia | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |0% | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;" |Schueler (1983)<ref>Schueler, T. 1983. Washington Area Nationwide Urban Runoff Project. Final Report. Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments. Washington, DC. </ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | colspan="2" style="text-align: center;" |'''<u><span title="Note:This estimate is provided only for the purpose of initial screening of LID practices suitable for achieving stormwater management objectives and targets. Performance of individual facilities will vary depending on site specific contexts and facility design parameters and should be estimated as part of the design process and submitted with other documentation for review by the approval authority" >Runoff Reduction Estimate*</span></u>''' | ||

| + | |colspan="2" style="text-align: center;" |'''45% on [[Soil groups|HSG A or B soils]];''' | ||

| + | '''10% on [[Soil groups|HSG C or D soils]]''' | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |} | ||

==Construction== | ==Construction== | ||

| Line 71: | Line 154: | ||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Bioswales]] |

*[[Check dams]] | *[[Check dams]] | ||

| − | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

[[Category:Infiltration]] | [[Category:Infiltration]] | ||

[[Category:Green infrastructure]] | [[Category:Green infrastructure]] | ||

Latest revision as of 14:49, 26 October 2023

This article is about installations designed to capture and convey surface runoff along a vegetated channel, whilst also promoting infiltration.

For underground conveyance systems which promote infiltration, see Exfiltration trenches.

Overview[edit]

Swales are linear landscape features consisting of a drainage channel with gently sloping sides. Underground they may be filled with engineered soil and/or contain a water storage layer of coarse gravel material. Two variations on a basic swale are recommended as low impact development strategies, although using a combination of both designs may increase the benefits:

Bioswales are sometimes referred to as 'dry swales', 'vegetated swales', or 'water quality swales'. This type of BMP is form of bioretention with a long, linear shape (surface area typically >2:1 length:width) and a slope which conveys water and generally contains various water tolerant vegetation,

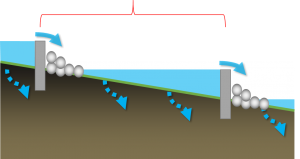

Enhanced grass swales are a lower maintenance alternative, but generally have lower stormwater management potential. The enhancement over a basic grass swale is in the addition of check dams to slow surface water flow and create small temporary pools of water which can infiltrate the underlying soil.

Grass swales are a relatively common landscape feature already and a great opportunity for retrofit, to reduce flow and improve water quality by encouraging settling and infiltration behind a series of check dams.

Retention swales can be imagined as linear, sloped dry ponds. They typically make relatively small contributions to water volume and quality control than many other BMPs, but they may feature as part of a site-wide treatment train approach.

Take a look at the downloadable Enhanced Grass Swales Factsheet below for a .pdf overview of this LID Best Management Practice:

Swales are an ideal technology for:

- Sites with long, linear landscaped areas, such as parking lots

- Connecting with one or more other types of LID

| Property | Bioswale | Enhanced grass swale |

|---|---|---|

| Surface water | Minimal Any surface flow can be slowed with check dams |

Ponding is encouraged with check dams |

| Soil | Filter media required | Amendment preferable when possible |

| Underdrain | Common | Uncommon |

| Maintenance | Medium to high | Low |

| Stormwater benefit | High | Moderate |

| Biodiversity benefit | Increased with native planting | Typically lower |

Planning Considerations[edit]

Enhanced swales and in some cases bioswales include check dams that can be designed to pond substantial volumes of water on the swale surface between flow events, so provide both stormwater conveyance and infiltration functions. For information about constraints to infiltration practices, and approaches and tools for identifying and designing within them see Infiltration. For guidance on infiltration testing and selecting a design infiltration rate see Design infiltration rate.

A linear design (surface area typically >2:1 length:width) is a common feature of swales:

- An absolute minimum width of 0.6 m is required for bioswales to promote healthy plant growth, and to facilitate construction,

- Grassed swales are usually mown as part of routine maintenance, so the cross section will be triangular or trapezoidal in shape with maximum side slopes of 1:3. The minimum width for this type would be 2 m. See Best cross sections

Swales may be graded along longitudinal slopes between 0.5 - 6 %:

- Between 1 - 6 %, check dams are recommended to bring the compensation gradient <1 %.

- Slopes > 6% can accommodate a series of stepped bioretention cells, each overflowing into the next with a spillway.

For a table summarizing information on planning considerations and site constraints see Site considerations.

Design[edit]

Pretreatment and inlets

To minimize erosion and maximize the functionality of the swale, sheet flow of surface water should be directed into the side of the BMP. Gravel diaphragms, vegetated filter strips and shallow side slopes are ideal. Alternatively, a series of curb inlets can be employed, where each has some form of flow spreader incorporated. Single point inflow can cause increased erosion and sedimentation, which will damage vegetation and contribute to BMP failure. Again, flow spreading devices can mitigate these processes, where concentrated point inflow is required.

Inspection and Maintenance[edit]

Maintenance requirements for enhanced grass swales, and swales is similar to vegetated filter strips and typically involve a low level of activity after vegetation becomes established. Grass channel maintenance procedures are already in place at many municipal public works and transportation departments. These procedures should be compared to the recommendations provided on the Inspection and Maintenance: Enhanced Swales page to assure that the infiltration and water quality benefits of enhanced grass swales are preserved.

Routine roadside ditch maintenance practices such as scraping and re-grading should be avoided at swale locations. Vehicles should not be parked or driven on grass swales. For routine mowing, the lightest possible mowing equipment should be used to prevent soil compaction.

For swales located on private property, the property owner, resident or manager is responsible for maintenance as outlined in a legally binding maintenance agreement. Roadside swales in residential areas generally receive routine maintenance from homeowners who should be advised regarding recommended maintenance activities and ensure they do not build anything within or on the channel of the swale which could result in flooding or pooling on theirs or their neighbours' properties.

Take a look at the Inspection and Maintenance: Enhanced Swales page by clicking below for further details about proper inspection and maintenance practices:

Performance[edit]

An evaluation of swales and roadside ditches was published by STEP in 1999. The project page and additional tools are available here.

Bioswales[edit]

While few field studies of the pollutant removal capacity of bioswales are available from cold climate regions like Ontario, it can be assumed that they would perform similar to bioretention cells. Bioretention provides effective removal for many pollutants as a result of sedimentation, filtering, plant uptake, soil adsorption, and microbial processes. It is important to note that there is a relationship between the water balance and water quality functions. If a bioswale infiltrates and evaporates 100% of the flow from a site, then there is essentially no pollution leaving the site in surface runoff. Furthermore, treatment of infiltrated runoff will continue to occur as it moves through the native soils.

| LID Practice | Location | Runoff Reduction* | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioswale without underdrain | Washington | 98% | Horner et al. (2003)[1] |

| Scotland | 94% | Jefferies (2005)[2] | |

| Bioswale with Underdrain | Maryland | 46 to 54% | Stagge (2006)[3] |

| Bioretention without underdrain | China | 85 to 100%* | Gao, et al. (2018)[4] |

| Connecticut | 99% | Dietz and Clausen (2005) [5] | |

| Pennsylvania | 80% | Ermilio (2005)[6] | |

| Pennsylvania | 70% | Emerson and Traver (2004)[7] | |

| Bioretention with underdrain | |||

| Ontario | 64% | CVC (2020)[8] | |

| Maryland and North Carolina | 20 to 50% | Li et al. (2009) [9] | |

| North Carolina | 40 to 60% | Smith and Hunt (2007)[10] | |

| North Carolina | 33 to 50% | Hunt and Lord (2006) [11] | |

| Runoff Reduction Estimate* | 85% without underdrain;

45% with underdrain | ||

Click on the citations above to view the performance of these features based upon specifics (i.e. drainage area to size ratio to achieve the reduction mentioned) in the table.

Enhanced grass swales[edit]

See Performance section on Enhanced swale page link above for additional information.

Recent research indicates that a conservative runoff reduction rate of 10 to 20% can be used depending on whether soils fall in hydrologic soil groups A/B or C/D, respectively. The runoff reduction rates can be doubled if the native soils on which the swale is located have been tilled to a depth of 300 mm and amended with compost to achieve an organic content of between 8 and 15% by weight or 30 to 40% by volume. The main contributing factors that influence runoff reduction rates for swales are:

- Native soil types

- Slope

- Vegetative cover and,

- Length of the swale.

| LID Practice | Location | Runoff Reduction* | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass Swale | Brampton | 15 to 35%, | STEP (2018)[12] |

| Sweden | 40 to 55%, | Rujner et al. (2016)[13] | |

| Seoul, Korea | 40 to 75%, | Rujner et al. (2016)[14] | |

| Maryland | 59% | Davis et al. (2012)[15] | |

| Los Angeles | 52.5%, | Ackerman and Stein (2008)[16] | |

| Various Locations | 40% | Strecker et al.(2004)[17] | |

| France | 27 to 41% | Barrett et al. (2004)[18] | |

| Virginia | 0% | Schueler (1983)[19] | |

| Runoff Reduction Estimate* | 45% on HSG A or B soils;

10% on HSG C or D soils | ||

Construction[edit]

Galleries[edit]

Simple grass swales[edit]

Grass swale in CVC headquarters parking lot, Mississauga ON

Water distributed into a wide grass swale with a rock level spreader

Flow in this wide swale is being reduced by taller vegetation on some sections (See Manning's n)

Bioswales[edit]

Streetside swale in Seattle

This feature is a bioswale in that the underlying soil has been replaced with engineered filter media. The turf finish simplifies landscape maintenance. Brampton, ON

A bioswale located on Country Court Blvd., located in Brampton, ON> Read more about the performance of this feature and associated rpoject, by reading the following Grey to Green Conference Presentation, 2018. Dean Young - STEP, 2018

Bioswale located in Downsview Park, Toronto ON. with Check dams.

Grassed bioswale with Vegetated filter strips

Stone-lined bioswale with rock check dams located to helps slow the flow of water as it enter the system from the nearby roads. [[ STEP, 2017

Check dams[edit]

Enhanced swale with rocky check dams and a metal overflow grate in Northgate Mall parking lot, Seattle. Photo credit: MLSmith

Bioswale with rock check dams to slow down the water, encouraging infiltration. Note the biodegradable erosion control blanket still in place. LSRCA headquarters, 2017

A swale during a rain event, with concrete check dams, armourstone, mulch and Tall grasses to slow down moving water (as shown in the .gif file) to promote infiltration in the feature.

Also see Jen's Pinterest board of check dams

See Also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ Horner RR, Lim H, Burges SJ. HYDROLOGIC MONITORING OF THE SEATTLE ULTRA-URBAN STORMWATER MANAGEMENT PROJECTS: SUMMARY OF THE 2000-2003 WATER YEARS. Seattle; 2004. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.365.8665&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Accessed August 11, 2017.

- ↑ Jefferies, C. 2004. Sustainable drainage systems in Scotland: the monitoring programme. Scottish Universities SUDS Monitoring Project. Dundee, Scotland. https://www.climatescan.nl/uploads/projects/8126/files/1277/SNIFFERSR_02_51MainReport.pdf

- ↑ Stagge, J. 2006. Field evaluation of hydrologic and water quality benefits of grass swales for managing highway runoff. Master of Science Thesis, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Maryland. https://drum.lib.umd.edu/items/42be6ce6-e4ef-4162-a991-c273607d422d

- ↑ Gao, J., Pan, J., Hu, N. and Xie, C., 2018. Hydrologic performance of bioretention in an expressway service area. Water Science and Technology, 77(7), pp.1829-1837.

- ↑ Dietz, M.E. and J.C. Clausen. 2005. A field evaluation of rain garden flow and pollutant treatment. Water Air and Soil Pollution. Vol. 167. No. 2. pp. 201-208. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.365.9417&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- ↑ Ermilio, J.F., 2005. Characterization study of a bio-infiltration stormwater BMP (Doctoral dissertation, Villanova University). https://www1.villanova.edu/content/dam/villanova/engineering/vcase/vusp/Ermilio-Thesis06.pdf

- ↑ Emerson, C., Traver, R. 2004. The Villanova Bio-infiltration Traffic Island: Project Overview. Proceedings of 2004 World Water and Environmental Resources Congress (EWRI/ASCE). Salt Lake City, Utah, June 22 – July 1, 2004. https://ascelibrary.org/doi/book/10.1061/9780784407370

- ↑ Credit Valley Conservation. 2020. IMAX Low Impact Development Feature Performance Assessment. https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2022/03/rpt_IMAXreport_f_20220222.pdf

- ↑ Li, H., Sharkey, L.J., Hunt, W.F., and Davis, A.P. 2009. Mitigation of Impervious Surface Hydrology Using Bioretention in North Carolina and Maryland. Journal of Hydrologic Engineering. Vol. 14. No. 4. pp. 407-415.

- ↑ Smith, R and W. Hunt. 2007. Pollutant removals in bioretention cells with grass cover. Proceedings 2nd National Low Impact Development Conference. Wilmington, NC. March 13-15, 2007.

- ↑ Hunt, W.F. and Lord, W.G. 2006. Bioretention Performance, Design, Construction, and Maintenance. North Carolina Cooperative Extension Service Bulletin. Urban Waterways Series. AG-588-5. North Carolina State University. Raleigh, NC.

- ↑ Sustainable Technologies Evaluation Program. Effectiveness of Retrofitted Roadside Biofilter Swales - County Court Boulevard, Brampton. Technical Brief. https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2020/11/CC-Bioswale-Tech-brief-2018-FINAL.pdf. https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2020/11/CC-Bioswale-Tech-brief-2018-FINAL.pdf

- ↑ Rujner, H., Leonhardt, G., Perttu, A.M., Marsalek, J. and Viklander, M. 2016. Advancing green infrastructure design: Field evaluation of grassed urban drainage swales. Modélisation/Models-Contrôle à la source/Source control. http://documents.irevues.inist.fr/bitstream/handle/2042/60477/3B7P03-124RUJ.pdf

- ↑ Rujner, H., Leonhardt, G., Perttu, A.M., Marsalek, J. and Viklander, M. 2016. Advancing green infrastructure design: Field evaluation of grassed urban drainage swales. Modélisation/Models-Contrôle à la source/Source control. http://documents.irevues.inist.fr/bitstream/handle/2042/60477/3B7P03-124RUJ.pdf

- ↑ Davis, A.P., Stagge, J.H., Jamil, E. and Kim, H. 2012. Hydraulic performance of grass swales for managing highway runoff. Water research, 46(20), pp.6775-6786. http://www.jstagge.com/assets/papers/Hydraulic%20performance%20of%20grass%20swales%20for%20managing.pdf

- ↑ Ackerman, D. and Stein, E.D. 2008. Evaluating the effectiveness of best management practices using dynamic modeling. Journal of Environmental Engineering, 134(8), pp.628-639. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Eric-Stein-2/publication/228910558_Evaluating_the_Effectiveness_of_Best_Management_Practices_Using_Dynamic_Modeling/links/0912f509278915fc77000000/Evaluating-the-Effectiveness-of-Best-Management-Practices-Using-Dynamic-Modeling.pdf

- ↑ Strecker, E., Quigley, M., Urbonas, B., Jones, J. 2004. State-of-the-art in comprehensive approaches to stormwater. The Water Report. Issue 6. August 15,2004.

- ↑ Barrett, M.E. 2008. Comparison of BMP Performance Using the International BMP Database. Journal of Irrigation and Drainage Engineering. September/October. pp. 556-561

- ↑ Schueler, T. 1983. Washington Area Nationwide Urban Runoff Project. Final Report. Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments. Washington, DC.