Siting and layout of development

The site layout is determined in part by the opportunities and constraints of the natural heritage system. The location and configuration of elements, such as streets, sidewalks, driveways, and buildings, within the framework of the natural heritage system provides many opportunities to reduce stormwater runoff. The goals of the site layout are to provide a functional and livable urban form while minimizing environmental impact. The techniques below highlight some of the ways in which site layouts can minimize their hydrologic impacts and preserve natural drainage patterns.

Strategies[edit]

Fit the design to the terrain[edit]

Using the terrain and natural drainage as a design element is an integral part to creating a hydrologically functional landscape.[1] Fitting development to the terrain will reduce the amount of clearing and grading required and the extent of necessary underground drainage infrastructure. This helps to preserve pre-development drainage boundaries which helps to maintain distribution of flows. Generally, siting development in upland areas will take advantage of lowland areas for conveyance, storage, and treatment.

Open space and clustered development[edit]

Clustering development increases the development density in less sensitive areas of the site while leaving the rest of the site as protected community open space. The open space can be undisturbed natural area or actively used recreational space. Features that often characterize open space or clustered development are smaller lots, higher density of structures in one area of a site, shared driveways, and shared parking. From a stormwater perspective, clustered development reduces the amount of impervious surface, reduces pressure on buffer areas, reduces the construction footprint, and provides more area and options for stormwater controls including LID practices.[2]

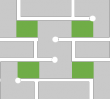

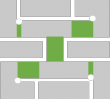

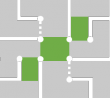

Street network designs[edit]

Certain roadway network designs create less impervious area than others. The figure from the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (2002) demonstrates that loop and cul-de-sac street patterns require less area for streets. These layouts by themselves may not achieve the many goals of urban design. However, used in a hybrid form together or with other street patterns, they can meet multiple urban design objectives and reduce the necessary street area.[3]A study comparing different road network designs for a hypothetical community showed a fused grid pattern can reduce impervious cover by 4.3% compared to a traditional neighbourhood design.[4]

Reduce roadway setbacks and lot frontages[edit]

The lengths of setbacks and frontages are a determinant for the area of pavement, street, driveways, and walkways, needed to service a development. Municipal zoning regulations for setbacks and frontages have been found to be a significant influence on the production of stormwater runoff. A study of residential parcels in Madison, Wisconsin found that reducing setbacks by 3 m and frontages by 5.5 m resulted in a 14% reduction of stormwater runoff.[5]

References[edit]

- ↑ Prince George’s County. 1999. Low Impact Development Design Strategies: An Integrated Design Approach. Prince George’s County, MD.

- ↑ Center for Watershed Protection (CWP). 1998. Better Site Design: A Handbook for Changing Development Rules in Your Community. Ellicott City, MD.

- ↑ Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC). 2002 (Revised 2005, 2007). Residential Street Pattern Design. Research Highlight: Socio-Economic Series 75.

- ↑ Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC). 2007. Research Highlight: A Plan for Rainy Days: Water Runoff and Site Planning. Socioeconomic Series 07-013. Ottawa, ON.

- ↑ Stone, B. and Bullen, J. 2006. Urban Form and Watershed Management: How Zoning Influences Residential Stormwater Volumes. Environmental and Planning B: Planning and Design. 33: 21-37.